Macro Watch - Global trade risks and Dutch exports

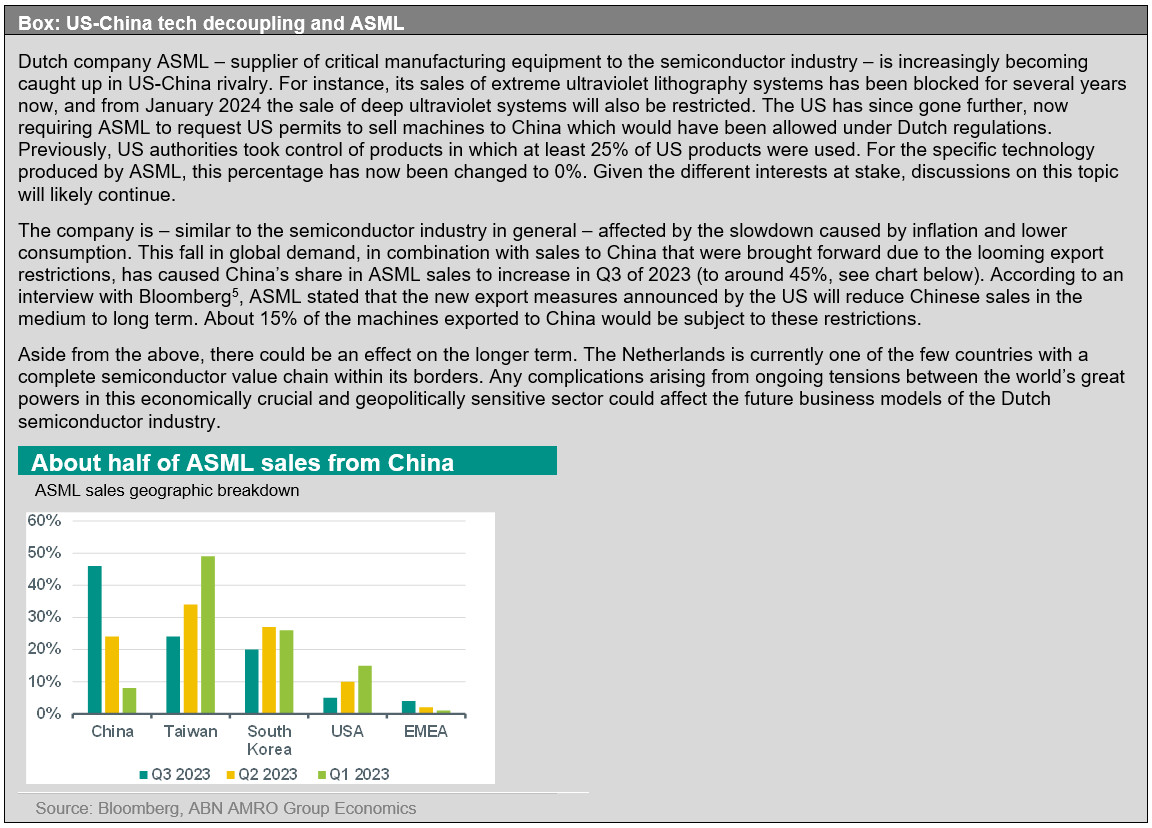

Global trade and manufacturing is still in recession territory. Although there are signs of bottoming out, a sharp rebound in global industry is not likely at the moment. Against this backdrop, Dutch exports have been falling. Still, the fading of bottlenecks in global supply chains is good news for Dutch exporters and importers. Despite the Netherlands being an open, trade-oriented economy, exports have been resilient to shocks. We look at the impact of US-China tech decoupling on the Netherlands, including on semiconductors/ASML.

I GLOBAL TRADE – RECENT DEVELOPMENTS AND OUTLOOK

Global trade still in ‘recession territory’

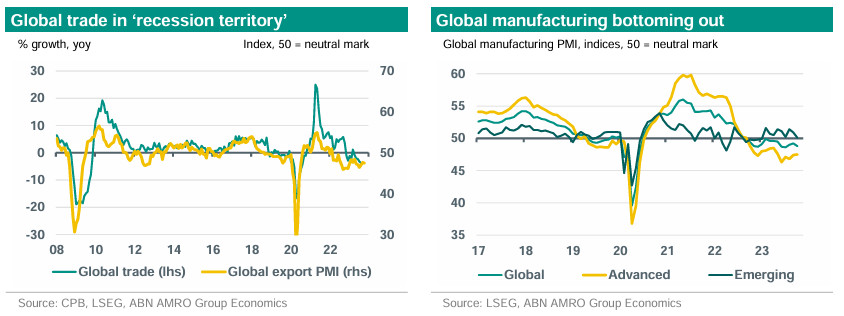

Following a post-pandemic rebound, global trade (measured by CPB’s global trade volume index) has slowed sharply since late 2022 and stayed in ‘recession territory’ so far this year. Although this index rose by 0.3% mom in August 2023, it still remained 4% below its peak reached in September 2022. This slowdown is primarily driven by the loss of momentum in global GDP growth, following the sharp tightening of monetary policy in the developed economies. China’s reopening from Zero-Covid did contribute to a rebound in Q1-2023, but that has proven quite short-lived so far.

In previous publications, we already anticipated a clear slowdown in global trade (see for instance our March 2023 update Global Trade: As the world turns). The forward-looking exports sub-index of the global manufacturing PMI did already drop below the neutral 50 mark separating expansion from contraction in March 2022, just after the start of the war in Ukraine, and reached a trough of 45.9 in September 2022. Although this subindex has bottomed out since, for now it is clearly still in contraction territory.

Outlook: Sharp rebound in global trade and manufacturing not likely at the moment

Developments in global industry and trade tend to go hand in hand. Not surprisingly, global industry has also been in recession territory since late 2022, with the global manufacturing PMI below the neutral mark since September 2022. In recent months, we have seen some bottoming out of this index. Although we do not forecast PMIs on a longer term basis, we expect any rebound in global trade and manufacturing to be modest in the coming months, given that we still expect a clear slowdown in the US, and ongoing economic sluggishness in the eurozone. Still, the stimulus to investment via the US’s Inflation Reduction Act and Europe’s recovery fund may help to offset the drag from weaker consumption. A bottoming out of domestic demand in China, following ongoing piecemeal monetary easing and targeted support, should also help.

The fading of bottlenecks and imbalances in global supply chains is good news for exporters/importers

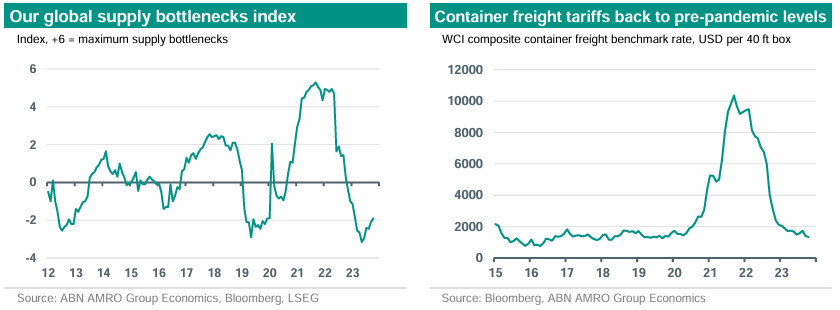

During the pandemic years, global trade was regularly disrupted by supply-side problems, such as the closure of terminals at some Chinese ports, or lack of staff to offload containers at US ports. Moreover, imbalances between global supply and demand for goods were exacerbated by a shift in global demand from services to goods during the pandemic, but also as a result of stimulative monetary and fiscal policies in the US and (to a lesser extent) other developed economies. The result of all this was that exporters and importers were faced with a sharp increase in global container tariffs, and longer delivery times in global production chains.

We developed an index to measure these types of bottlenecks and global imbalances in the supply of and demand for goods. This index showed a sharp increase during 2021, indicative of the increasing imbalances between supply and demand at the time.However, since mid-2022, our index has pointed to a sharp reduction in these imbalances. This is to a large extent due to a sharp cooling on the demand side, alongside a post-pandemic normalisation on the supply side; since late 2022 our index has been in ‘supply abundance’ territory. In line with this, container freight rates have fallen back to pre-pandemic levels, while delivery times for manufactured goods, including for electronics equipment, have normalised. All of this is good news for (Dutch) exporters and importers, offering some ‘compensation’ for the current weakness in momentum in global growth and trade.

II HOW ARE DUTCH EXPORTS FARING IN A CHALLENGING INTERNATIONAL ENVIRONMENT?

Dutch exports of goods falling on the back of stagnating global demand

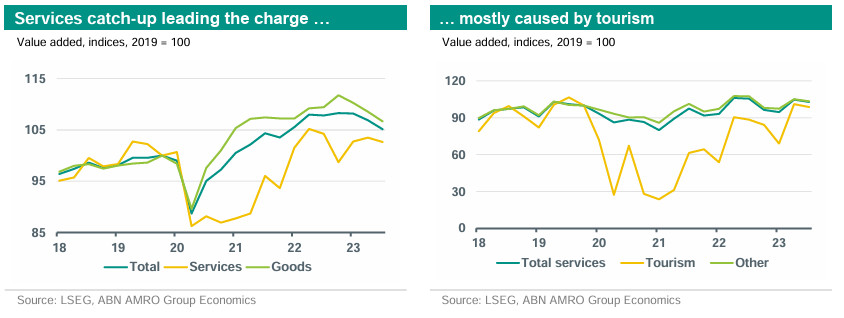

During the summer, the global economy proved quite resilient despite the headwinds from high inflation and consequently higher interest rates. Below the surface, however, differences between trading blocs are widening. The positive outlier in terms of growth is the United States, where consumption has shown resilience. The opposite picture is true for the eurozone, where growth has been broadly stagnant for the past four quarters already. We expect further stagnation the eurozone and the pace of growth to weaken US in the coming quarters, whereas we foresee a bottoming out of growth in China following a weak Q2. The weakness in global trade and industry (as described above) is making itself felt in the Netherlands. The slowdown in the global demand for goods (alongside the energy crisis) has already pushed Dutch industry into recession, as Dutch exports of goods have fallen over the past three quarters. Re-exports in particular experienced a sharp contraction. Dutch-made goods exports declined relatively less sharply.

Services exports, on the other hand, increased in the first half of 2023 due to a rebound in tourism. Services exports have benefitted from the post-pandemic recovery, after being hit by the decline in travel during the pandemic. Third quarter results indicate that this catch-up is behind us. We also see reasons for a structural change making a full return to the pre-pandemic trend in services unlikely. First, the pandemic seems to have created a structural change in preferences, leading for instance to less business travel. Second, tax rules have changed which make export-related intellectual property investment less attractive. We expect Dutch exports to remain weak in the last quarter of 2023.

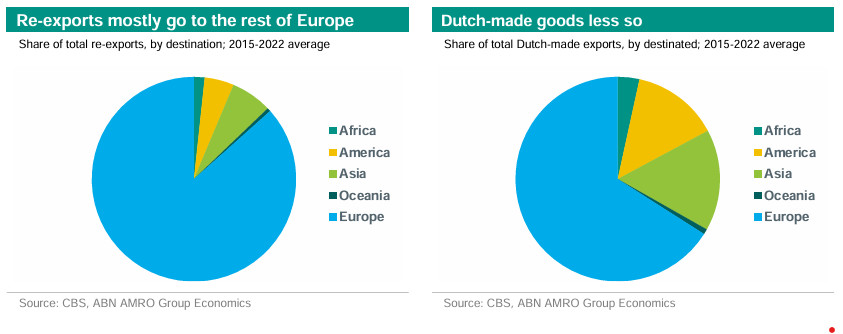

Re-exports taking the lead

As a highly trade-oriented country, the Netherlands is deeply integrated into international value chains. The Netherlands can be seen as the gateway for goods into the EU from the rest of the world (see left-chart below for the destinations of Dutch re-exports). Roughly 85% of Dutch re-exports go to the rest of Europe, compared with 65% of Dutch-made goods. A recent CPB study (1) concludes that re-exports were the engine of exports over the past two years, with re-export growth stronger than that of Dutch produced goods. As the value added of re-exports is only about 1/5 that of domestically produced goods, a larger share of re-exports in the total has meant a declining contribution from exports to GDP overall.

Dutch trade has been surprisingly resilient to past shocks

Despite the Netherlands being an open economy and heavily dependent on developments abroad, Dutch exports have exhibited resilience to shocks (2). Since 1980, the market share of Dutch exporters in world trade has been remarkably stable, albeit fluctuating from time to time. Despite the rise of Asian tigers, the BRICS, and in recent times with negative trade shocks from the pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war, the Netherlands has held on to its market share. Due to Brexit, Dutch exports to the UK declined, but this was concentrated in re-exports – mostly re-exports of Asian goods to the UK. The hit to Dutch GDP is thus smaller than the export decline suggests.

Two explanations for this resilience in previous downturns have been provided by the study. The first is that not only location mattered (think of easy access to sea, rivers or land), but firm-specific factors (such as firm size, activity type, diversification) mattered more when explaining the trade recovery after the Global Financial Crisis. The second reason is found on the import side and relates to ease of diversification. As we saw during the pandemic, supplier substitution prevented what could have become a prolonged trade downturn This is due to globalisation: trade diversification has increased, as well as the opportunities for doing so. In the short-term, diversifying was more challenging, and only half to two-thirds of trade downturn was prevented by substitution. However, in the medium-term, the increased range of alternative suppliers and markets created resilience during the pandemic, and lowered the risks associated with relying on a smaller group of trading partners.

These two examples illustrate resilience in previous trade downturns, but show only part of the picture. Recent shocks also expose risks regarding competitiveness. Think for instance of the rising unit labour costs, or the dependency on energy imports causing higher energy costs for the Dutch industrial sector (read more here). These or similar factors could put pressure on the Dutch competitive position.

Does the Netherlands no longer get a cold when Germany sneezes?

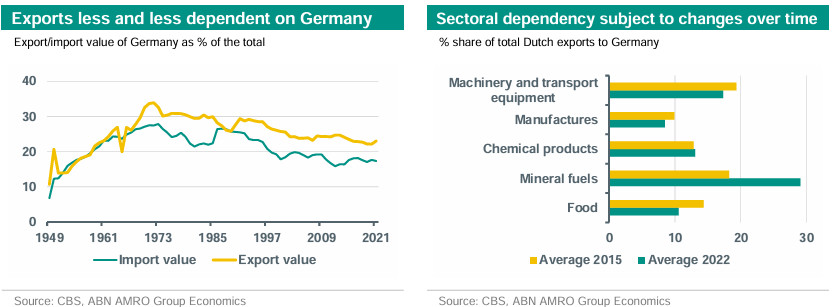

There is a saying that when Germany sneezes, the Netherlands gets a cold. This describes the historically tight trade relations between the two countries. Recently, a study by the CPB dives into this relation (3), and concludes that Dutch good exports grew strongly despite the economic stagnation that we saw in Germany in 2021-22. Germany is still the main market for Dutch exports, but the share of Dutch exports to Germany has declined (see below). Indeed, though German car production has underperformed in recent years, most Dutch industry only derives a small share of its total income from the German car industry. The most dependent sector is the Dutch car-industry which makes up around 1% of total Dutch output and earns only around 5% of its output from exports to Germany. As a result, the impact on the Dutch economy has been limited.

III THE IMPACT OF US-CHINA TENSIONS ON THE NETHERLANDS

US-China tech decoupling under a ‘Small Yard, High Fence’ strategy …

The US-China relationship has become less volatile under president Biden compared to the Trump era, and therefore the impact on the global economy and markets has been more benign, but tensions have not disappeared. Whereas Trump’s approach was mercantilist, transaction-based and unilateral, Biden’s approach is more ideologically-based and multilateral. Biden did not step up the bilateral trade tariffs imposed by Trump, but also did not reduce them. Under Biden, the US administration has tightened a wide range of trade and investment restrictions versus China, partly building on what was set in motion under Trump. What is more, Biden succeeded in rebuilding old alliances with strategic partners, both on the economic and military front. The US for instance was able to convince countries like Japan and the Netherlands to join in restricting the export of semiconductor and related equipment to China (see our October Global Monthly, Six urgent questions on China for more background).

US-China relations have been tested this year by events such as the spy balloon incidents, developments in the Taiwan Strait and China’s position versus Russia. Still, over the past few months, steps have been taken to prevent the bilateral relationship going into a downward spiral. This was illustrated by visits of high ranking US officials to Beijing, with a Biden-Xi meeting potentially scheduled in November. The message from officials is that the US is not aiming for a full decoupling from China. Instead, the US is using a ‘Small Yard, High Fence’ strategy: clear export and investment restrictions (‘High Fence’) are targeting a selected number of sectors (‘Small Yard’) that are sensitive from a national security perspective.

… is increasingly impacting the Netherlands

The Netherlands is increasingly becoming caught up in dynamics related to US-China relations. Think for instance of the US regulations on ASML (see the box below), but also China’s decisions around critical raw materials on which many industries rely. As a highly trade-oriented country, the Netherlands is highly exposed to trade conflicts (4). The direct risks of US-China rivalry to the Dutch economy are via trade links with either country. Indirect risks are related to global trade and the effects of the ‘derisking’ strategy, which could cause companies to gradually adjust their supply chains.

We think the macroeconomic impact of the US-China trade tensions on the Netherlands remains limited, but scarcity of critical raw materials could – for instance – lead to price rises, policy challenges and operational delays (read more here). Moreover, on average in the years 2015-22, about 8% of the total Dutch goods import originated from China and similarly from the US. From China, around 55% is machinery and transport equipment (mostly consisting of computers, phones, solar-panels etc.). Which means that sectors or developments dependent on these imports could be affected, such as the telecom sector or the energy transition which is dependent on solar panels. However, about two-thirds of all imports from China are re-exported. In terms of Dutch goods exports, on average in the years 2015-22, about 4.2% go to the US and 2.1% to China. Most of the value added from trade with China to the Dutch economy comes from exports of Dutch-made goods. Over 2015-20, exports of Dutch-made goods to China contributed on average 0.5% to GDP, while re-exports make a near negligible contribution. Overall, the direct exposure of Dutch exports is relatively small and – even in a continued de-risking scenario – we would expect exports to China to continue.

(1) CPB, Wederuitvoer motor achter stijging Nederlandse export, augustus 2023

(2) For this section we rely on two studies: 1) P. van Bergeijk, Nederlandse positie ook in onzekere tijden goed gehandhaafd, ESB, 18 december 2022 and 2) S. Creemers, M. Jaarsma, J. Rooyakkers, Vooral minder door- en wederuitvoer naar het VK sinds Brexit, ESB, 21 december 2022.

(3) CPB, Wederuitvoer motor achter stijging Nederlandse export, augustus 2023

(4) F. van der Putten & M. Sie Dhian Ho, Aiming to avoid painful dilemmas: the Netherlands and US-Chinese rivalry, Clingendael institute, Europe in the Face of US-China Rivalry, January 2020

(5) C. Koc, ASML Bookings Plunge 42% Amid Continued Slump in Chip Sector (4), Bloomberg, 18 November 2023