Global Monthly - Six urgent questions on China

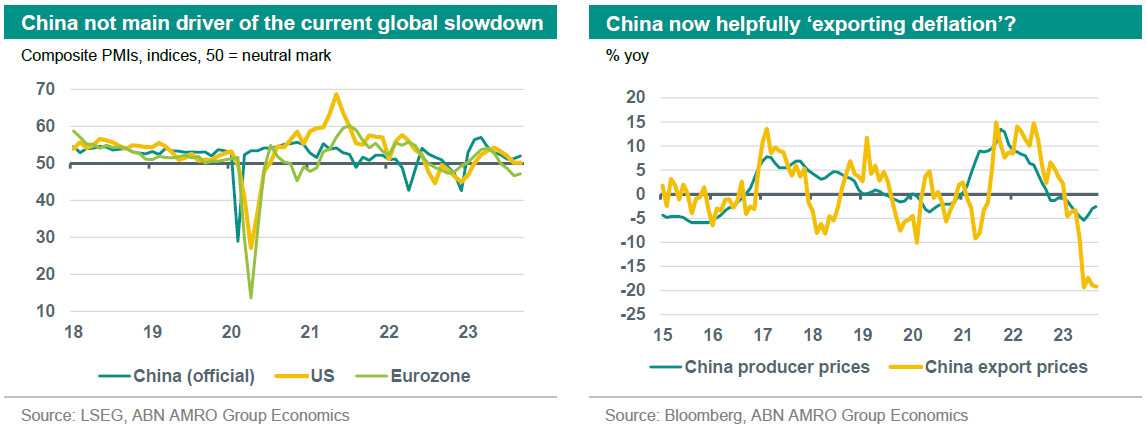

The main driver of the global growth slowdown is the spike in inflation and interest rates, not China, but a sharper reopening rebound would have cushioned global growth more than it has. In this special Global Monthly, we tackle six urgent questions surrounding China's recovery and what it means for the global economy. Cyclically, the Chinese economy already passed the trough, but headwinds remain: from property sector woes, to post-zero-Covid scarring, and the global slowdown in demand for goods / rotation back to services, next to some other (structural) challenges. A silver lining of China’s slowdown is less inflation, but at the current juncture this effect is limited. Given how China-EU/US relations are evolving, we delve into how this is impacting tech/EV sectors.

Global View: China’s disappointing recovery is both friend and foe for the global economy

Geopolitics is once more dominating the headlines following the escalation between Israel and Hamas, as the Russia-Ukraine war enters its 21st month. Going forward, events in the Middle East could become a key driver of oil prices (see our Spotlight on this). In our last Global Monthly, we looked at the potential impact of a bigger oil price surge. Rising bond yields are another dominant theme, and as things stand, we think the tightening in financial conditions will do part of the job of central banks in dampening demand and inflation. In this Monthly, we delve into another hot topic: China. Over the summer months, signs of distress in the Chinese property sector added to fears of a more serious and prolonged slowdown. In a Q&A format, we explore why China’s reopening rebound has disappointed and to what extent the economy is now stabilising. We then look at the impact of China’s growth dynamics on US and eurozone growth and inflation. Finally, we take stock of developments in China-US & EU relations. A challenging year lies before us. Alongside presidential elections in the US and Taiwan, a surge in China’s EV exports to Europe could trigger a trade spat between Brussels and Beijing.

Introduction

As we saw during the pandemic years, developments in China have the potential to shock the global economy. Earlier this year, we downplayed potential spillovers of China’s reopening rebound to global growth somewhat, as this would primarily benefit non-tradeables (services) sectors1). In fact, due to several factors, China’s reopening rebound has been under-whelming so far, and China-related investor sentiment seems to have turned from moderately bullish to outright bearish. In this note, we tackle six urgent questions that are still important for financial markets/our stakeholders in our view.

We start by looking more closely at the factors behind China’s faltering rebound (Q1). Next, we analyse the recent signs of stabilisation and judge where China’s growth is heading to (Q2). We then turn to the impact on global growth (Q3). A silver lining to China’s sluggishness is the dampening impact on global inflationary pressures (Q4). Finally, we turn a little bit more ‘thematic’, as we take stock of relations between China and the US/EU, which also have the potential to affect the outlook (Q5 and Q6).

Q1: After a rapid reopening rebound in Q1-2023, China’s recovery has been underwhelming. Why?

Following three years of strict Zero-Covid policy with recurrent lockdowns, earlier this year the general expectation was that abandonment of this policy would result in a sharp reopening rebound that would cushion global growth. Although we did see a clear rebound in Q1-2023, particularly for services most hit by Zero-Covid such as transport, tourism and entertainment, this proved quite short-lived, with the rebound faltering from Q2-2023 onwards. Why?

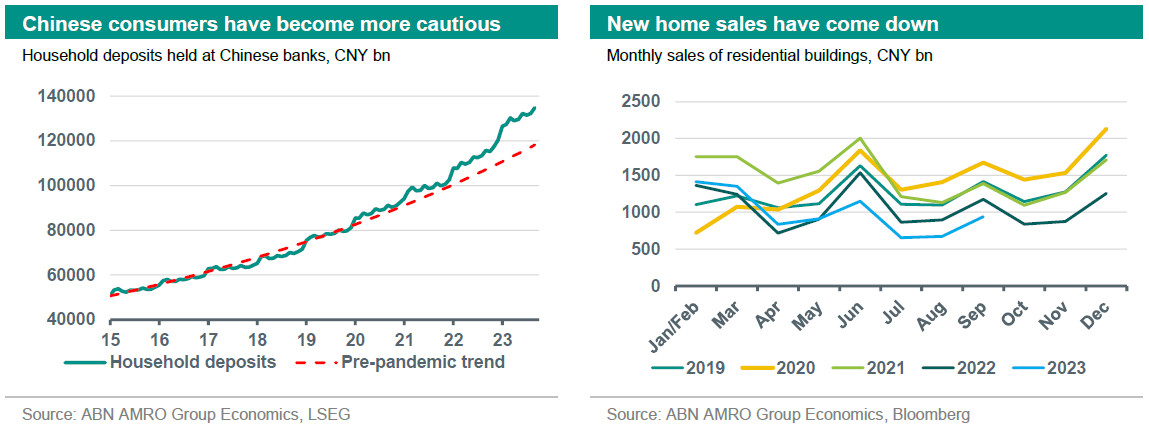

As highlighted in earlier publications, Zero-Covid exit was a crucial policy shift, but did not take away all headwinds1). In addition, a reopening rebound does not mean that an economy will start firing on all cylinders immediately. In fact, several headwinds have intensified in the course of this year. First of all, the scarring from previous stringent policies (Zero-Covid, regulatory crackdown on internet platforms, three red lines policy in real estate) proved quite serious, and it led – coupled with other factors adding to uncertainty – to more cautiousness amongst consumers and private firms. Consumer confidence dropped, consumers propped up savings and became less willing to buy big ticket items, including new homes. And private investment slowed materially, to a large extent impacted by weak property investment.

Second, all of this also contributed to the intensification of headwinds from the property sector. The uptick in new home sales in Q1-2023 proved short-lived, and that added to financing constraints for property developers. Moreover, although the government stepped up targeted support and eased to some extent the sharp edges of its three red line policies aimed at reducing leverage in property, they made clear their long-term goal of downsizing the property sector in light of the longer-term trends in demographics and urbanisation. This has also hit the so-called land finance development model, in which local governments raise cash from land sales and use that to fund infrastructure projects via local government financing vehicles (LGFVs). Repeated signs of financial distress at major developers such as Country Garden Group (next to Evergrande), rising loan defaults and signs of contagion to financial institutions with risky exposures to the sector did not help to stabilise sentiment either. Although some signs of stabilisation are visible recently, and we expect the government to continue with targeted support to curtail systemic risks, drags from the property sector will remain for the foreseeable future.

Third, while China normally is an important engine for global growth (see Q3), the other side of the coin is that the country was not immune to the slowdown in global demand stemming from the sharp hike in global inflationary pressures and the subsequent hike in policy rates. In addition, global demand has rotated back towards services from goods following the post-pandemic period of normalisation in most countries, which is on balance negative for China given that it still is the global manufacturing hub for goods. As a result, the remarkable export strength shown during the pandemic years has faded; instead, annual growth of Chinese exports has been in contraction mode for most of this year so far.

Q2: Where is China’s growth heading to?

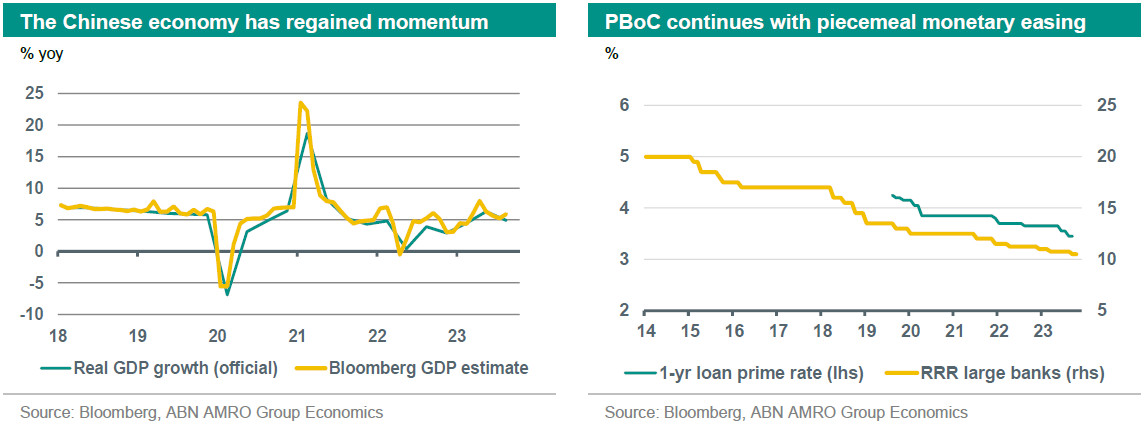

From a cyclical point of view, we believe that the trough in China’s economic slowdown following the reopening rebound in Q1-2023 was in July, and that since then growth momentum has picked up again, despite ongoing signs of financial distress in the property sector. This assumption is partly based on the expectation that the PBoC will continue with piecemeal monetary easing, and the government with adding targeted support, with a special focus on the property sector.

Real GDP growth accelerated to 1.3% qoq in Q3, up from a downwardly revised 0.5% in Q2 (old: 0.8%). This reflects improvements at both the supply and the demand side. In annual terms, real GDP slowed from 6.3% yoy in Q2 to 4.9% in Q3, but that mainly reflects a base effect from last year. In Q3-2022, China’s economy showed a strong rebound (+3.7% qoq) from the sharp dip in Q2-2022 following the broad Omicron-related lockdowns. The latest GDP data confirm that the government’s growth target of 5% for 2023 is within reach, in line with our expectations.

Moreover, activity data for August and September also confirm that the economy is bottoming out, as continued piecemeal monetary easing and targeted support starts filtering through. China’s manufacturing PMIs (from Caixin and NBS) were both above the neutral 50 mark again in September, for the first time since February. Growth of retail sales and industrial production has picked up since July. And the unemployment rate dropped to a two-year low of 5.0% in September. Although annual growth of exports and imports remains in contraction mode, the contraction is becoming shallower, as recent foreign trade data show some improvement. Lending volumes have clearly picked up from the seasonal dip in July. Recent CPI and PPI data show that deflationary pressures are gradually fading. All in all, Bloomberg’s monthly GDP estimate has risen to 5.9% yoy in August/September, up from 5.2% in July.

That said, the recovery is still uneven and fragile. Consumer confidence is yet at historically low levels. Services PMIs have come down compared to Q1, the gap between manufacturing and services PMIs has narrowed rapidly, and Caixin’s composite PMI dropped to a 2023 low in September. What is more, property market data remain weak and property related sentiment shaky, with ongoing debt distress amongst property developers including giants Evergrande and Country Garden. Annual growth of residential property sales and property investment fell deeper into contraction territory in September, although home sales showed some improvement on a monthly basis. Ongoing weak sentiment is also visible in China’s equity and FX markets.

All in all, notwithstanding the short-term cyclical improvement, the Chinese economy will continue to be faced for some time with fierce headwinds from the property sector and related debt issues (amongst property developers, banks and local governments), from the global growth slowdown and from ongoing tensions with the US/EU/West (also see Q5 and Q6). Longer-term challenges also relate to demographics (ageing, a shrinking population/labour force) and climate change (Beijing aims to peak CO2 emissions before 2023 and to reach carbon neutrality before 2060). Coupled with Beijing’s policy shift away from growth maximalisation towards goals related to national security and self-sufficiency, we expect China’s structural slowdown to continue and annual growth to fall below 5% from 2024 onwards (leaving aside cyclical corrections).That said, we think comparisons with Japan’s ‘lost decade’ are a bit overblown/premature at the moment (also see our previous report Will the Chinese Dragon keep flying).

Q3: What is the impact of China’s growth trajectory on the US and Europe?

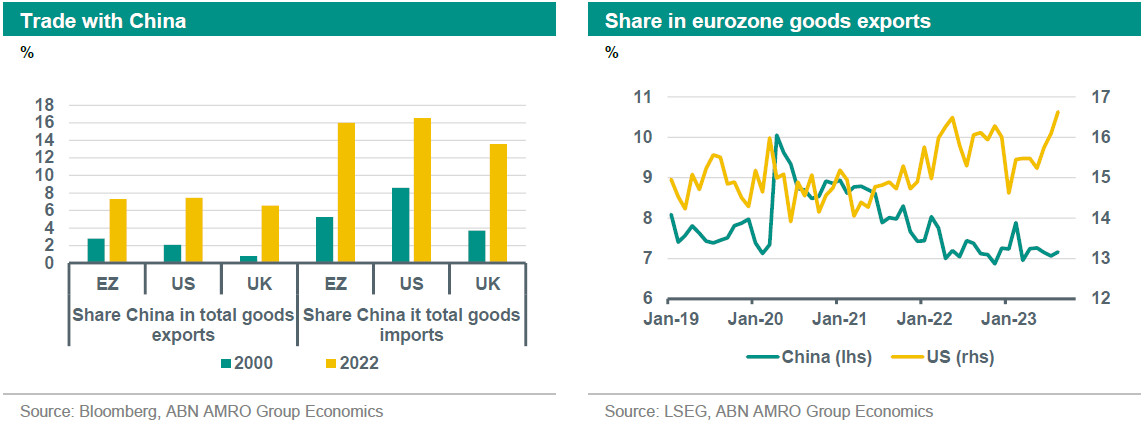

We think the impact of China’s disappointing rebound through the foreign trade channel has been larger for the eurozone than for the US. In addition, in our view, China is not the main driver of the current global growth slowdown, that's the spike in inflation and subsequent sharp hike in policy rates by a wide range of central banks. Still, a stronger domestic reopening rebound in China would have cushioned global growth to some extent.

The US and Europe have intense trade relations with China. Since China joined the WTO in 2001, the share of China in foreign trade has risen rapidly, with all countries/regions recording trade deficits with China. The main products that China exports to the US is computers, broadcasting equipment, office machine parts and other manufactured products. In reverse, the US’s exports to China mainly consist of food products (e.g. soy beans, corn), integrated circuits and cars. China’s exports to Europe mainly consists of computers, electric batteries, broadcasting equipment, office machines and machine parts, whereas Europe mainly exports cars, motor vehicles and motor vehicle parts, beauty and fashion products, packed medicaments and food products to China.

Changes in bilateral trade flows are influenced by a number of factors. For instance, longer-term trends in foreign trade can shift due to innovation, changes in technology or shifts in the availability and price of factors of production, such as labour or raw materials. Moreover, bilateral trade flows can be permanently impacted by policy measures such as the imposition of tariffs or quantitative trade restrictions. In contrast, shorter-term trade flows tend to be mainly influenced by cyclical changes in domestic demand in the two countries/regions. For instance, China’s exports to the eurozone contracted during the years 2012-2013, when the eurozone was in recession and domestic demand in the region contracted, whereas China’s exports to the US and the rest of the world expanded in those years. In reverse, the slowdown in China’s domestic demand in the first half of this year, will have had a downward impact on European exports to China.

Indeed, eurozone exports to China have been significantly weaker than eurozone exports to the US in the first half of this year, when domestic demand in the US grew robustly. This can be illustrated by the rising share of the US and the falling share of China in total eurozone exports (see graph). Besides the share of China in total exports, the impact on economic growth of changes in China’s growth will also be influenced by the importance of foreign trade in total economic activity. Goods exports have a significantly higher share in GDP in the eurozone (20%) than in the UK (17%) or US (8%). This means that an economic slowdown or acceleration in China will probably have the largest economic impact on the eurozone.

Q4: What is the impact of China’s growth trajectory on global inflation?

China’s disappointing post-pandemic recovery has a silver lining, in the current environment: less inflation. While the importance of China in the global inflation story is sometimes overstated, it is still crucial. There are two main channels through which China impacts global inflation, and specifically, inflation in our focus areas – the eurozone and US: 1) Chinese goods exports; 2) China’s demand for natural gas and oil (also other commodities, but energy is most important for inflation).

Outside of the economics profession, we tend to think of inflation as something that largely concerns physical items. This is because, intuitively, it is easier to quantify the value of a good – which is made up of very tangible inputs – than it is a service. Hence, you see media headlines recently suggesting that China – as the ‘factory of the world’ – is helpfully ‘exporting deflation’ once again, relieving pressure on central banks as they continue to fight well-above target inflation. It is true that China is helping to dampen or even lower global goods prices, and if anything, the falls in Chinese producer prices over the past year understates the extent of this: as we describe below, Chinese export prices have fallen even more sharply in recent months. However, imported Chinese goods make up a relatively small part of the overall consumption basket in the eurozone and the US, and so the impact of this only goes so far.

Goods have around a 20% weight in the eurozone and US inflation baskets, while Chinese imports make up the equivalent of just 10% of overall goods (ex-food) consumption. To illustrate China’s impact on inflation: a 10% rise (or fall) in Chinese exported goods prices would raise (lower) inflation by 0.2 percentage points (pp). In reality, the weakness in the Chinese economy combined with stuttering global demand has meant export price falls of closer to 20% y/y in recent months (see chart on front page) – more than unwinding the worst of the pandemic bottlenecks-induced jump in prices. The simple rule of thumb calculation therefore suggests 0.4pp lower inflation in the eurozone and US than would otherwise have been the case if Chinese export prices had stayed stable2). In a more normal inflationary environment, a 0.4pp hit would be significant, but in the current environment of highly elevated inflation, this is a relatively small driver. For comparison, housing rents in the US currently contribute around 2.4pp to inflation, while at the height of the energy crisis last year, the jump in gas prices contributed around 4pp to inflation in the eurozone.

A more meaningful – though harder to quantify – factor has been the more indirect impact of China’s tepid recovery on global energy prices. A big fear at the outset of 2023 was that Europe may not be able to secure enough LNG for the coming winter, as China’s (then expected) post-pandemic demand surge risked diverting supplies. This ultimately didn’t materialise, as China’s recovery turned out to be weaker than expected. As a result, while prices in the global LNG and European TTF gas market have still been volatile, prices are still far lower than in 2022, and expected to remain so. Although some upward pressure from increased Chinese demand is likely going forward, we expect a relatively modest rise in TTF year ahead gas prices to €60/MWh in 2024. It is a similar story for oil prices. Chinese demand for oil has certainly recovered this year, but its impact on markets has been muted. Indeed, global oil demand has been weaker than expected at the start of this year, prompting OPEC producers to curb supplies in order to prop up prices. While both oil and gas prices rose in the second half of the year, and could yet see further shocks from Middle East instability, China has been less of a driver than it would have been if its recovery had been much stronger. Overall, China’s inflation impact via the energy channel can be thought of as reducing upside risks rather than materially altering the base case for inflation.

Ultimately, as we described in our September Global Monthly, a much more important driver of the medium term inflation outlook is labour markets, given that wage growth is the main determinant of services inflation – which has a much bigger weight in inflation baskets. While China’s weaker recovery is certainly a big help for central banks in their inflation fight, the unwinding of labour market tightness is the real game changer for the outlook.

Q5: How will US-Chinarelations evolve in a challenging year, and how will that affect the outlook?

As we had expected at the time of US President Biden’s election in 2020, US-China relations have remained tense in recent years, since the US desire to act to contain China’s rise has become bipartisan. It is true that the relationship has been less volatile under Biden compared to the Trump era, and therefore the impact on the economy and markets has been more benign. However, from a strategic Chinese perspective, the direction that the Biden administration has taken (or has continued with) is perhaps even more challenging. Whereas Trump’s approach was mercantilist, transaction-based and unilateral, Biden’s approach is more ideologically-based and multilateral. Biden did not step up the bilateral trade tariffs imposed by Trump, but also did not reduce them. Under Biden, the US administration has tightened a wide range of trade and investment restrictions versus China, partly building on what was set in motion under Trump. Think of restrictions on incoming and outgoing FDI, on exports of semiconductors and related machines, and indirectly through the Inflation Reduction Act, aspects of which seek to protect US industry from foreign competition (including in areas related to the energy transition). Last but not least, Biden did succeed in rebuilding old alliances with strategic partners, both on the economic and military front. The US for instance was able to convince countries like Japan and the Netherlands to join in tightening the rules for semiconductor exports to China.

After a Biden-Xi summit in late 2022 aimed at smoothing relations, US-China relations have been tested this year by events such as the spy balloon incidents, developments in the Taiwan Strait and China’s position versus Russia (see also our special note here). China’s positioning in the recent Israel/Hamas conflict may also not help with repairing relations. Still, over the past few months, steps have been taken to prevent the bilateral relationship going into a downward spiral. This was illustrated by visits of high ranking US officials to Beijing, with a Biden-Xi meeting potentially scheduled in November. The message from officials is that the US is not aiming for a full decoupling from China. Instead, the US is using a ‘Small Yard, High Fence’ strategy, as US National Security Advisor Sullivan has called it: clear export and investment restrictions (‘High Fence’) are targeting a selected number of sectors (‘Small Yard’) that are sensitive from a national security perspective.

Going forward, the window of opportunity to manage US-China relations looks to be narrowing. The campaign for the 2024 US presidential elections has started, and candidates will be wary of being portrayed as ‘soft on China’. Despite former president Trump’s legal woes, it appears that this may not be enough to prevent either his candidacy nor his potential re-election, with leading rival for the Republican nomination Ron DeSantis performing poorly in the polls. A Trump re-election in November 2024 would raise the risk of a more abrupt deterioration in relations if he does return to power. Meanwhile, presidential elections in Taiwan are scheduled for January 2024. The candidate of the pro-independence Democratic Progressive Party, Lai Ching-te is leading in the polls so far. He has been criticised by Beijing, which favours the pro-China Kuomintang party, but the rise of the more ‘in between’ Taiwan’s People’s Party may change the political landscape to some extent. All in all, a DPP victory in January may add to risks surrounding the Taiwan Strait.

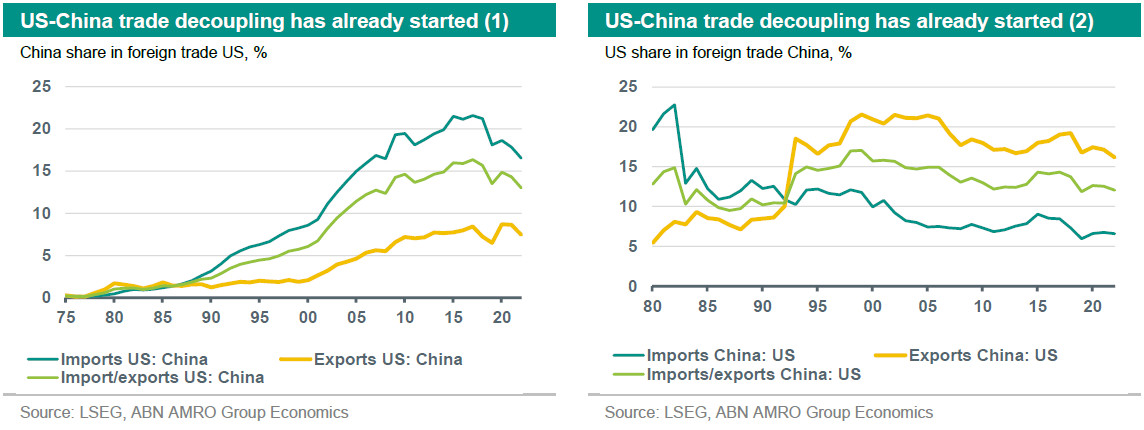

Meanwhile, bilateral trade data show that the US-China trade relationship already shows a degree of decoupling since Trump’s trade war started, although bilateral numbers probably overstate this given evasion practices (underinvoicing and rerouting of trade). What is more, bilateral tensions have led to a higher geopolitical risk premium, which is hindering portfolio flows (dominated by the US) towards China, and is impacting the investment decisions of global multinationals (with for instance Apple ramping up iPhone production in India). This is contributing to a gradual shift in global supply chains. We expect such shifts to remain gradual, given the large (vested) interests at stake, although a flaring up in cross-Strait tensions could of course accelerate this process of decoupling versus China.

Q6: With China’s EV exports to Europe rising, is a EU-China trade spat near?

Compared to the US (see Q5) , the European Union (EU) has so far been taking a more balanced approach in reshaping its relationship with China. While Brussels has also started to rethink this relationship, it has not adopted a similar national security framework comparable to that of the US. The EU also does not feel the same pressures as the US regarding issues related to global tech leadership. In essence, the EU is weighing the trade-offs between continued economic cooperation (including on issues related to climate change) versus concerns over strategic competition, national security and human rights differently than the US. Whereas the US is aiming at a targeted tech decoupling versus China from a national security perspective, the EU describes its approach as derisking the EU-China relationship and related supply chains. The EU’s more measured approach also reflects different interests and opinions in individual member states. That said, the EU has also taken various measures versus China over the past few years and/or is working on plans to enable the imposition of further restrictions.

Whereas the US has raised bilateral tariffs, stepped up investment and export restrictions and imposed targeted sanctions versus China over the past few years (see Q5), the EU has gone less far. The EU did not follow the US in imposing broad import tariffs versus China, which the Trump-administration did several years ago. The EU did adopt a screening mechanism for incoming Chinese FDI, but it is clearly softer than the US equivalent. Brussels did not introduce common strategic export restrictions versus China, although its toolkit is being expanded. The EU has already worked out an ‘anti-coercion’ mechanism that can be used vis-à-vis countries such as China. In the area of sanctions, Brussels imposed Xinjiang related sanctions on some Chinese officials in 2021, the first ones since 1989 (Tiananmen Square crackdown). The EU also imposed sanctions on a few Chinese firms that are being accused of delivering sensitive items to Russia, although the list was shortened after pushback from China. Earlier this year, the EU published its Critical Raw Materials Act, in which it sets targets for domestic capacity and aims to limit the supply from a single country by 2030.

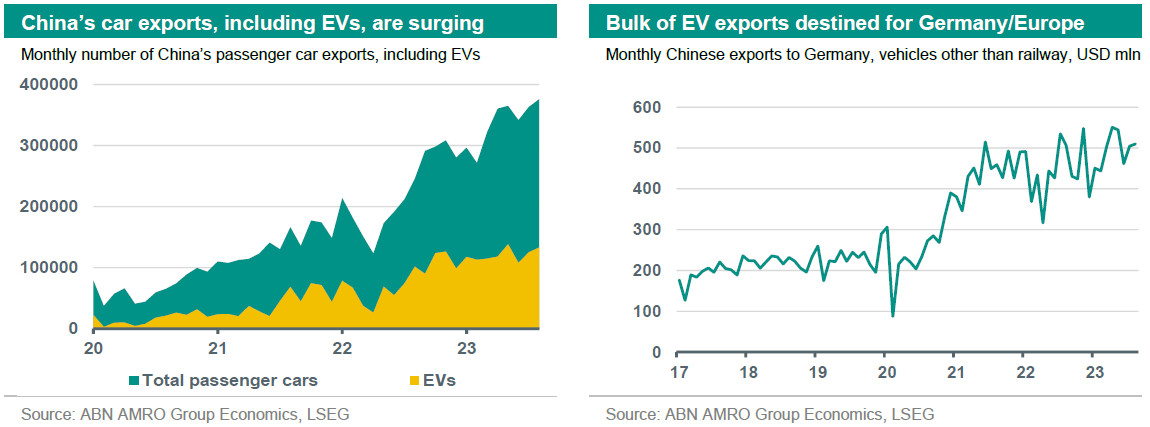

More recently, however, the EU trade-offs in managing its relationship with China seem to have shifted. In September 2023, the EU announced an investigation into potential Chinese subsidies granted to producers of electric vehicles (EVs). This follows the remarkable surge in China’s car exports over the past two years, including those of EVs, which is a result of the stepping up of production combined with a weakening of demand in China. The bulk of China’s EV exports is destined for Europe. According to the European Commission, China’s share of EVs sold in the EU is currently 8% and could rise to 15% in 2025. China’s exports of non-electric (internal combustion engine) cars have also risen sharply – partly reflecting a structural demand shift towards EVs –, but these cars typically go to Russia, Central Asia and other emerging markets.

The EU investigation started early October 2023, with a formal notice in the EU’s official journal. The probe will include all kinds of support measures (subsidies, grants, loans, tax rebates etcetera), will last for about one year and will cover the period October 2022-September 2023. At the end of the investigation, the EU will assess the level of government support in China’s EV industry and will decide on potential countervailing measures (such as raising import tariffs above the standard 10% for cars). China has criticised the investigation, pointing to the risks of disruptions to global automotive supply chains and to China-EU economic relations. Although the (electric) car industry is important for Europe and some measures may well be taken, depending on the outcome of the investigation, we expect Brussels to act carefully in this area, as it usually does given the broader interdependencies at stake, and with the possibility of Chinese retaliation in mind.

1) From our Global Monthly January 2023: “China’s abrupt exit from Zero Covid is expected to cushion slowing demand in advanced economies, but we do not expect it to be a game changer. The eurozone’s dependence on China consists mostly of industrial goods exports from Germany, which is linked to growth in China’s manufacturing sector. However, even before China’s Zero Covid exit, its manufacturing sector had already reopened for a large part, and this is reflected in the easing of supply side bottlenecks over the past year. At this point, then, China’s ‘reopening’ is to a significant extent a domestic services story. Moreover, China’s recovery is still constrained by weakness in the property sector and – related to that – weak credit growth …”

2) In reality, the falls in Chinese export prices may not be fully passed on if, for instance, the earlier rises in prices were not fully passed on, or if retailers think prices may rise again in future