Global Monthly -Will tight labour markets make inflation sticky?

In this monthly, we challenge our view that peak policy rate is in sight and pivots are on the cards later this year. Labour market developments present the most proximate risk to our monetary policy view. We assess the likelihood of wage-price spirals emerging from current tight labour markets and wage developments.

In the Euro area, short term wage acceleration is probable, but from employment growth is set to weaken, while unemployment will increase, reducing the risk that wage acceleration will be persistent, though the ECB will need to see evidence of these trends materialising before changing tact

In the US, temporary tightness from sectoral mismatches and worker shortages since the pandemic create upside risks to wages and inflation, which might make the Fed decide to go further than in our current base case.

A weakening economy should see labour markets turning down convincingly during the course of this year, which together with sharply lower inflation, should see central banks pivot

Regional updates: European economies show resilience to the energy crisis, with growth in Q4-2022 coming in stronger than expected. Still, for the Eurozone we expect moderate GDP contractions in the coming quarters, as interest rate hikes start to bite. For the Netherlands, we also expect weak growth in early 2023, but the Dutch economy will continue to outperform the eurozone in 2023-24.

In the UK, we view risks to inflation and Bank Rate tilted to the upside, reflecting industrial action.

Finally in China, the way is paved for a staged recovery in domestic demand and economic growth.

Over the last few weeks financial markets have been upwardly revising their view on where the peak in central bank policy interest rates will be, as well as how long they will remain in restrictive territory. This reflects recent better than expected macro data and decidedly hawkish commentary from central bank officials. These trends have been challenging our view that the peak is within sight and that a pivot towards rate cuts will follow by the end of the year. For such a scenario to play out, we would need to see very clear signs that inflation – especially the core – is coming down. While that is a necessary condition, it is not a sufficient one. We would also need to see signs that the labour market is materially weakening and hence that inflationary pressures will come down sufficiently over the medium term.

In this monthly we reassess the strength of labour markets as well as the pass-through channels to inflation. In what follows, we first take stock of labour markets by looking at various indicators to assess tightness, wage pressures and the passthrough of wages to inflation. Whether firms are willing and able to refrain from passing higher labour costs through to prices depends on competitiveness (willingness) and corporate profitability (ability). Finally, we consider global supply chain pressures to inflation. The final section presents the monetary policy implications.

Europe: short term tightness but cooling ahead

While all labour markets we consider are tight, it matters whether that tightness springs from exceptionally high demand, a lack of supply, or sectoral shifts since the pandemic. It matters for determining how much wage pressure it is generating and where wage growth will go over the course of the year.

Below trend demand with above trend supply of labour

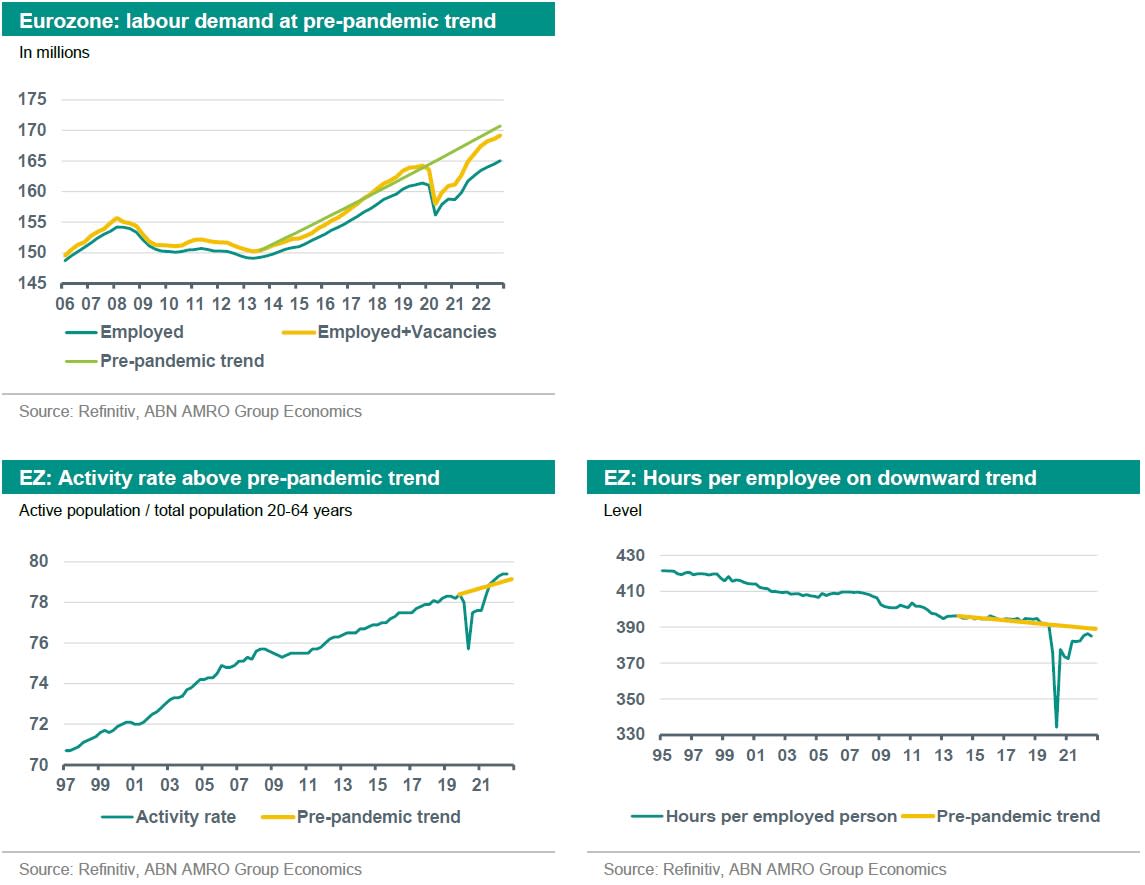

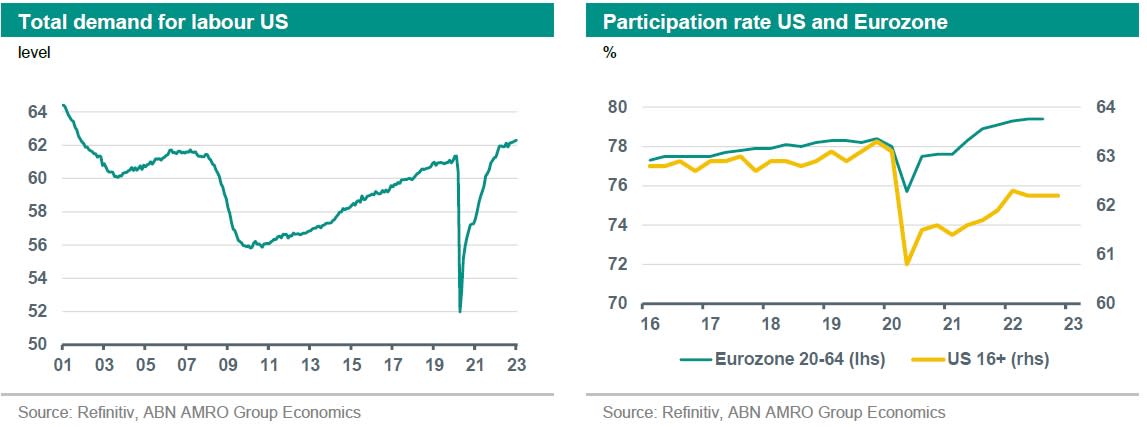

Starting with labour demand (total employment plus vacancies), the chart below shows that labour demand is above the pre-pandemic level, but it is below the pre-pandemic trend. Together with above trend labour participation, our judgement is that the Eurozone labour market is not that tight to start with on aggregate.

In addition, we see that in the first three quarters of 2022 the demand for labour slowed, from 0.8% qoq in 2022Q1, to 0.5% in Q2 and 0.2% in Q3.

The percentage of people between 20-64 who are at work or actively looking for work - has surpassed pre-pandemic levels (78.4%) in the 3rd quarter (79.4%). In comparison with the US, the Eurozone did not see its active population decrease as much, but rather saw its hours worked collapse during the pandemic on the back of job retention schemes. Since then, the number of hours worked per employee has bounced back. In 2022Q3, it still was below the pre-pandemic level, but roughly back in line with the downward trend of the last two decades.

Interest rate sensitive sectors start to unwind

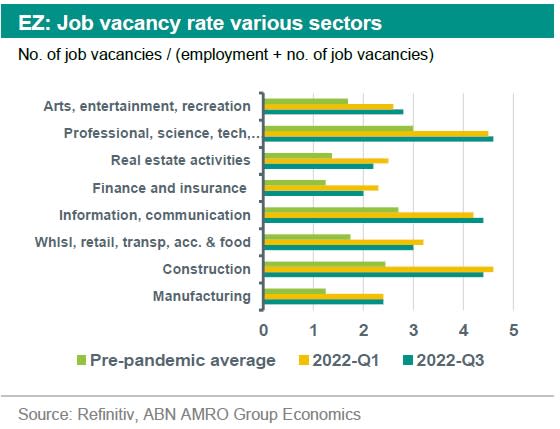

Based on the number of vacancies, most segments of the eurozone labour market still seem very tight, although tightness has moderated in some sectors during the course of 2022. The job vacancy rate for the whole economy declined in Q3, to 3.1%, down from 3.2% in 2022Q2 (pre-pandemic average is 1.8%). At the sector level, the job vacancy rate for the contact intensive parts of the services sector (e.g. accommodation, recreation, entertainment) increased between 2022Q1 and 2022Q3, whereas the job vacancy rate for the sectors where activity is most sensitive to monetary policy and developments in the housing market (e.g. finance and insurance, real estate), declined during those quarters. The vacancy rate in manufacturing stabilised between 2022Q1-Q3.

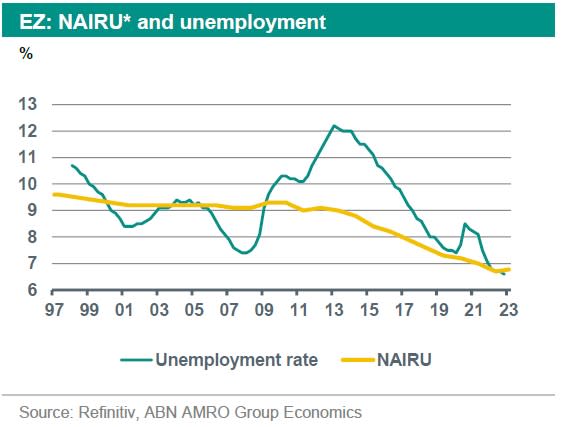

Unemployment rate close to (but not below) NAIRU

While unemployment has moved to a historic low of 6.6 percent in December 2022, the equilibrium unemployment (that estimates when unemployment levels become inflationary) has been moving down along with it since the eurozone crisis, as countries implemented labour market reforms and reforms to the social security and pension systems. These have helped to increase the activity rate in the Eurozone. According to estimates by the European Commission the unemployment rate was very close to the NAIRU at the end of 2022. This means that unemployment is almost at the level where it is inflationary. However, it is possible that the NAIRU has fallen below those estimates given that the impact of reforms continues to feed through.

* The non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) is the specific level of unemployment that is evident in an economy that does not cause inflation to increase. In other words, if unemployment is at the NAIRU level, inflation is constant. NAIRU often represents the equilibrium between the state of the economy and the labour market.

3 reasons for accelerating wages in the short term

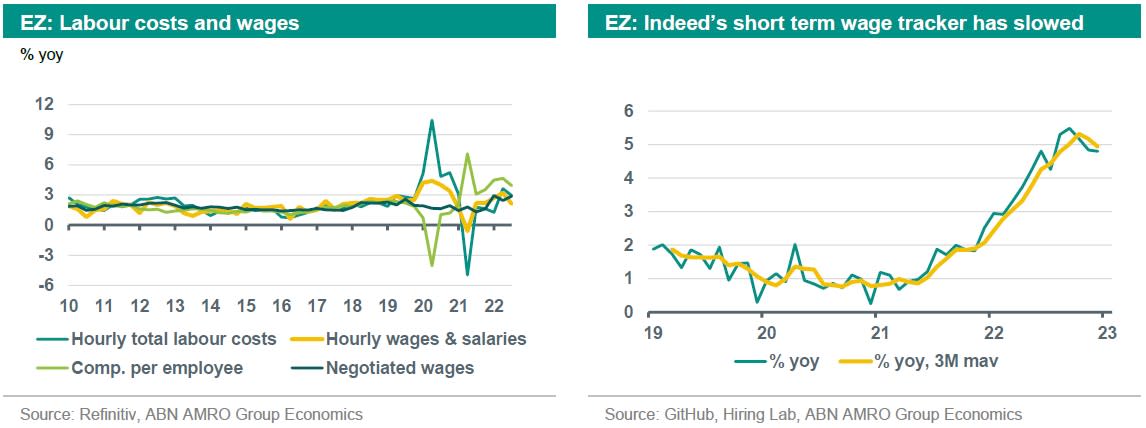

Wage growth in Europe has been on the rise since the end of the pandemic. Negotiated wages accelerated from 1.3 percent before the energy crisis to 2.9 percent in the third quarter of 2022. An alternative real-time measure for new jobs published by Indeed has moved substantially higher, to a recent peak of 5.5 % y-o-y in August 2022 which is well above the (3%) level consistent with 2% inflation. But even this measure suggests that wages inflation has started to ease in the last quarter of 2022.

While cooling of the European labour market is on the cards, in the short run, there are three factors that may still push up wage growth in the first few months of 2023 in specific sectors.

First, sectoral re-allocations - away from and then towards the leisure sector for example - raised churn-related vacancies and has created temporary sectoral tightness.

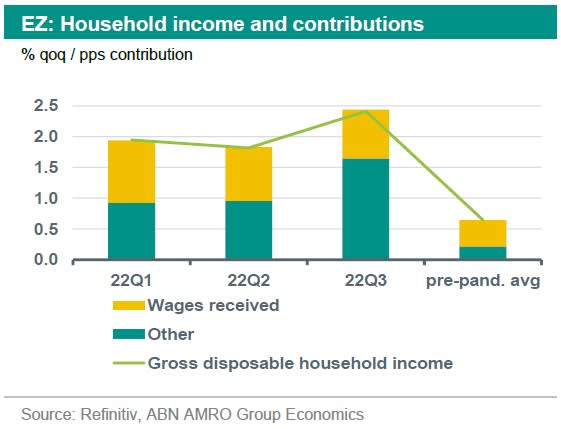

Second, a number of other income sources such as government support or income from the housing market have been boosting gross domestic household income. While government compensation is planned to be phased out in the coming months and housing prices have started to come down, these additional income sources may explain why services stayed remarkable resilient up until now. February services PMIs improved slightly to 53, indicating expansion. This resilient demand for services, could keep labour market tightness high and as such lead to an acceleration of wages in the coming months.

Third, as government compensation schemes are unwinding, labour unions might look at employers to compensate a larger share of the inflation burden of workers. This could create some temporary upside wage pressure as long as inflation is still high.

For the industrial sectors, the opposite holds. February’s manufacturing PMI signalled contraction (48.8) and the ECB reports easing labour shortages and lower demand for temporary staff by employment agencies. Indeed, the European Commission business and consumer survey shows that labour shortages have ceased to be the major worry for manufacturing firms.

While all three arguments for upward wage pressure are temporary and sector specific, negotiated wage growth is expected to accelerate in the next few quarters (i.e. 2023 H1), from 2,9 % in Q3 2022 to around 3.5-4% before starting to come down.

Eurozone wage growth to slow back to level consistent with inflation target by 2024

On the back of a moderate recession in Europe, a not that tight labour market to start with, early signs of cooling in manufacturing, already contracting fixed investment and the effects from past monetary tightening still coming down the line, employment is expected to come down while unemployment is to accelerate in the second half of 2023. Short term wage acceleration is expected to diminish during the course of next year. As a result, wage growth should slow down again from 3.5 to 4% in the first half of 2023 to 3% over the course of 2024. A level consistent with the ECB’s medium term inflation target.

US: stubborn worker shortages on top of sectoral mismatch

Supply shortages persist

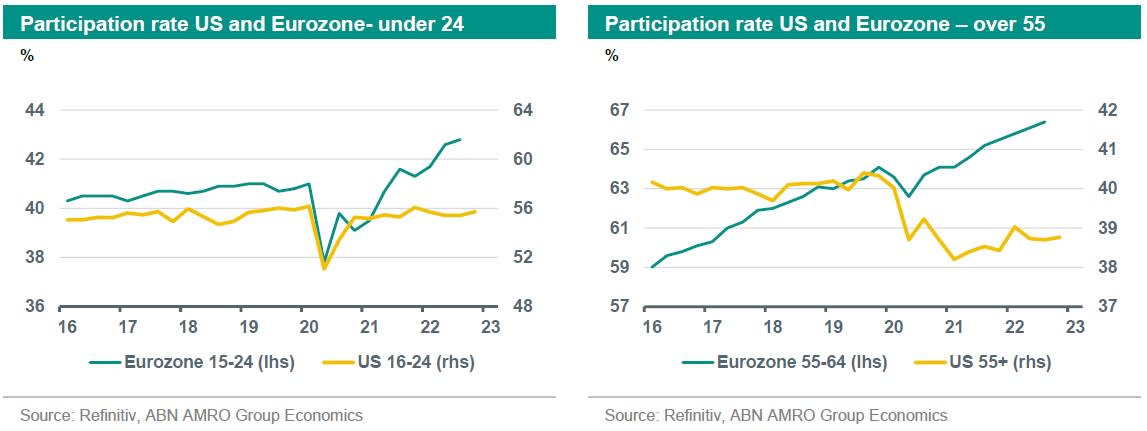

Tightness in the US labour market is not so much coming from the demand side. Total Employment plus vacancies have moved back to the pre-pandemic trend but not beyond. Moreover, the vacancy rate is declining. The tightness is mainly coming from supply shortage. In contrast to the Eurozone, participation in the US has remained well below pre-pandemic levels. Early retirement of older American workers is often mentioned as a reason for the low participation rate, but there also is a striking difference between the US and EU in the post pandemic rebound of activity amongst younger people. Whilst in Europe, younger workers returned back to the labour market at a pace beyond the pre-pandemic trend, in the US it even remained slightly below the pre-pandemic level.

Massive sectoral mismatch created temporary wage pressure

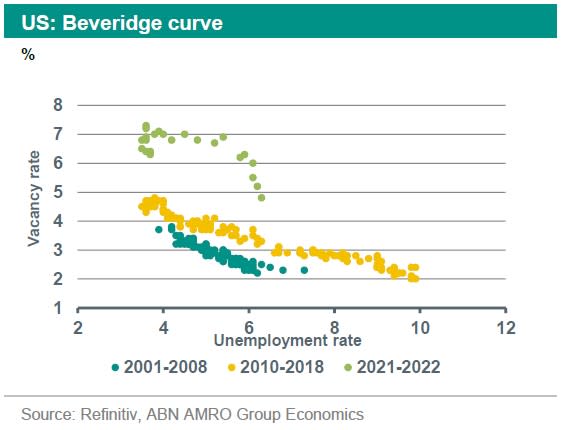

To assess potential sectoral mismatches the Beveridge curves is a useful tool. It plots the unemployment vis-à-vis vacancies. Close to peak tightness, the labour market swings to the upper left corner of the curve (with high vacancies and low unemployment). If the curve moves sideways to the right, this indicates sectoral mismatch, as vacancies stay open while unemployment is higher. The Beveridge curve of the US shows that de pandemic led to massive frictions in the labour market, as the green dots show that the curve is shifting sideways. Labour market frictions increased on the back of shifting consumer demand, which drove temporary shifts in labour demand (for instance from services to goods, and now back to services). While these labour market frictions are temporary as wages will eventually reallocate workers to the sectors with demand, it can in the short run drive wage increases.

With unemployment at a 5-decade low of 3.4%, the Congressional Budget Office estimates that unemployment has fallen below the threshold where it can easily become inflationary.

Medium term wage growth likely to come down

Our take is that the US labour market is now at the turning point. Wage growth has already come down significantly and layoffs are picking up. We expect wages to cool further in the next months. From its peak of over 6% (3m/3m saar), average hourly earnings were growing at a 4.4% (3m/3m annualised) pace as of January. This is only a little higher than the pre-pandemic peak. Moreover, given US long term productivity growth of 1.5 %, a cooling of wage growth to around 3.5% should suffice to be consistent with the Fed achieving its 2% inflation target.

Our base case is that despite resilient labour demand, the labour market has reached its turning point as investments are contracting, consumption is cooling and layoffs have started to tick higher. This also means that labour demand will slow, unemployment will begin rising and vacancies continue falling over the coming months.

The upside risk to this view is that if persistent labour hoarding occurs despite a cooling economy, demand could remain more resilient and wage growth could reaccelerate on this persistent tightness. There is however also a downside risk. The labour market could unwind more rapidly once a tipping point in layoffs is reached, which could set of a self-reinforcing dynamic of weaker employment driving lower consumption and hence weaker employment. This could then push down further on wage growth over the medium term.

Netherlands: extreme tightness is cyclical on top of structural

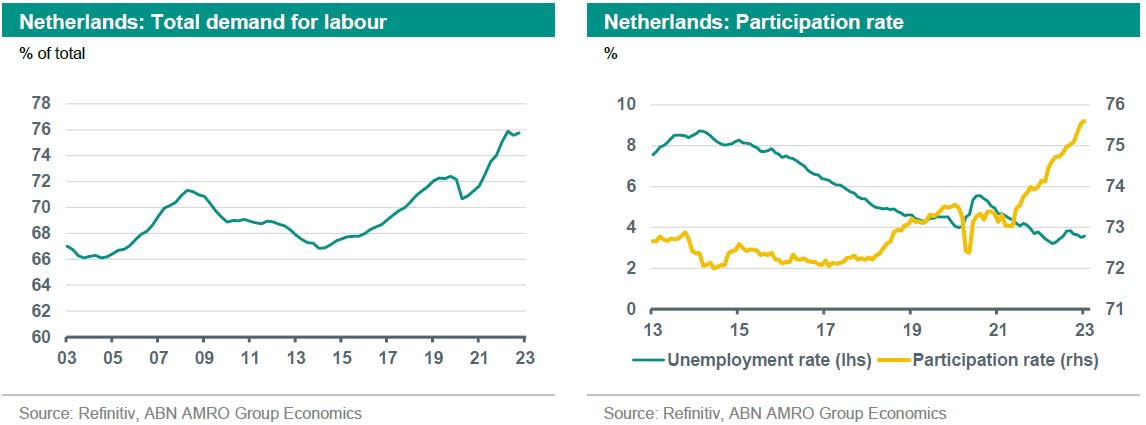

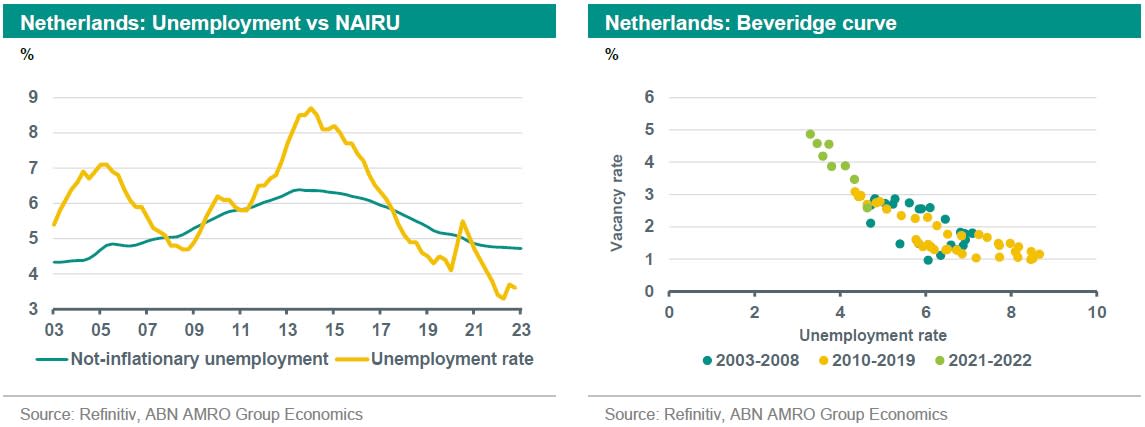

Dutch labour market tightness looks rather extreme to us, with unemployment deeply below the non-inflationary level of unemployment. In December 2022, unemployment decreased even further to 3.5%. The demand for labour is far beyond pre-pandemic trend, though the participation rate rose to 75.6% in January 2023, preventing even more tightening.

Besides temporary factors that are expected to unwind this year - such as the pandemic support that is keeping demand high and bankruptcies at a historic low – it is the structural tightness that could make employers reluctant to let go of workers even if revenues go down. To assess whether sectoral mismatches explain part of the tightness we analysed the Beveridge curve in the same way as we did for the US. This shows that there is no outward movement of the curve, suggesting that temporary tightness from a sectoral mismatch does not seem to play a large role.

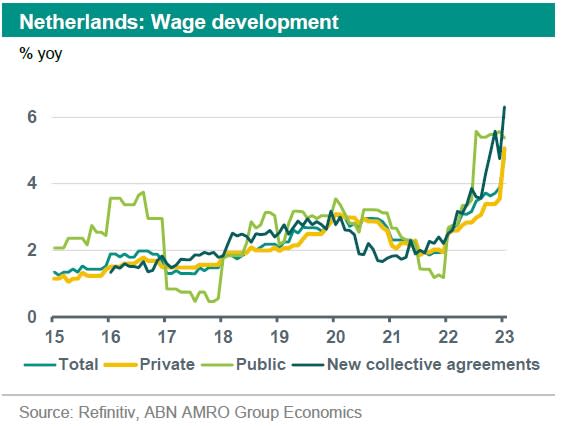

All these factors above make wage growth acceleration likely this year. Labour unions are asking for large increases, such as the FNV transport wage demand of 14,6%. While these wage demands do not appear likely, negotiated wage growth has already increased to 5 percent, which is well above historic levels. It is worth noting that wage growth was muted in the past even when unemployment fell to levels below the NAIRU (in 2019 for example).

Something else than tightness is playing into wages

Two other factors are playing into current successful wage growth negations: the first is inflation itself. Consumer Price Inflation peaked at 14.5% in September 2022 (versus 10,6% in the eurozone). While the Dutch CPI figure was partly distorted (see here why), it encouraged labour unions to ask for much more compensation than they had in previous years.

A second factor that played its part in the wage negotiations is government support. Throughout Europe gross disposable household income was massively supported by various government support schemes. For the Netherlands, these compensations schemes were in place as well, but the combination of extreme labour shortages and exceptionally high CPI figures has dominated negotiations.

Higher wages for longer in the Netherlands

In the Netherlands, wage growth of around 5% and new agreements closing above 6%, is way above the historic bandwidth of 1 to 3%. Given the structural tightness on the labour market, the long-term structure of labour agreements and the inflation figure itself pushing up the trend in new agreements, we expect wage growth to stay elevated for longer. This is rather remarkable, given the culture of wage moderation in the wage setting process that has kept wage growth confound to 3% even at times of very high labour shortages. The Dutch labour market looks therefore much more overheated that the Eurozone labour market. At the same time monetary policy is aligned with the Eurozone aggregate, which means that an easing of the Dutch labour market (over and above that expected from the eurozone) will have to come from fiscal unwinding of demand stimulating measures, such as the energy compensation schemes for households and for firms.

The pass-through of wages to inflation

With wage growth as high as 4.4% in the US, 5% in the Netherlands and 2.9% but rising in the Eurozone, the pass through to inflation and the re-emergence of a wage price dynamics has become relevant again. In the decade between the GFC and the pandemic, wages in Europe have been growing faster than productivity, resulting in higher unit labour costs, but this did not lead to much consumer price inflation. According to a study by the IMF, the disconnect between unit labour costs and inflation was due to 3 channels: subdued inflation and better anchored inflation expectations, more exposure to competition (either domestically or abroad), and higher aggregate corporate profitability (including when supported by access to cheaper inputs). Given the substantial changes that happened in recent years in these channels, we need to reassess whether such an outcome is likely this time around.

Inflation expectations add no munition to wage price spirals

If inflation expectations de-anchor, both firms and workers are likely to try and increase prices and wages. Looking at short- and medium-term inflation expectations for the US and the Eurozone, these seem well anchored. 1- and 2-year expectations rose substantially, but have eased towards the long run. Medium term inflation expectations have remained broadly in line with long run average. Inflation expectations thus do not pose a risk of a revival of the passthrough of wages to prices.

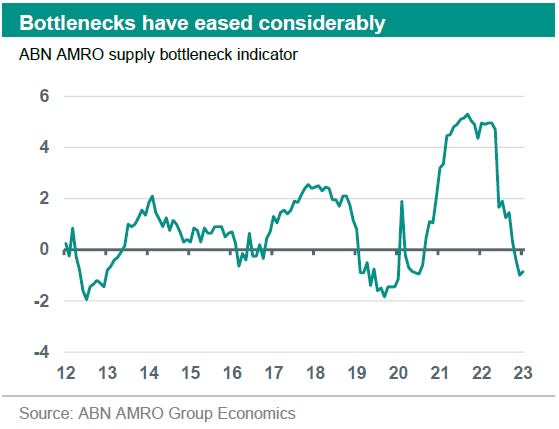

Supply bottlenecks resolved increasing competition

After the massive supply chain disruptions from the pandemic and the reopening, our ABN AMRO supply bottleneck indicator that combines many variables that capture these pressures, has eased back to pre-pandemic levels. This suggests that competitive pressures from global trade are back and are posing downside risks to the pass through of wages to prices. The broader trend of deglobalisation could in the longer run lower competitive pressures.

Profit margins signal competitive pressures still alive

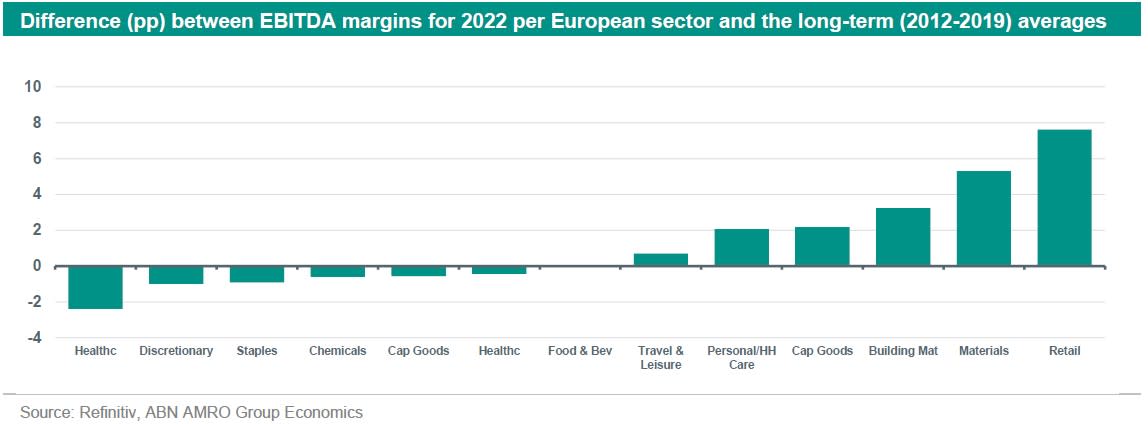

Apart from construction and retail sectors, corporate profit margins did not substantially increase in 2022 compared to their long-term average. This indicates that only in retail and construction firms have been able to raise prices more than their costs. Even for these sectors the recent turbulence in supply chains may have justified for example firms in the construction sectors to add some buffers to their profits in case of shortages. Moreover, equity market pricing suggests that these profit margins will not be sustained. An important caveat to keep in mind is that SME’s make up a large part of the European economy and are not included, although recent ECB research suggests that European SMEs financial resilience is rather strong.

Conclusion and monetary policy implications

On balance, we see no clear evidence of wage growth passing through to prices more easily than before. Most important is that medium term inflation expectations remain well-anchored. With our assessment that wages are already cooling in the US and that in the second half of 2023 wage growth will start to come down in the Euro area as well, we think that the danger of wage-price spirals keeping inflation from coming down is not very high. That said, the risks that temporary frictions or government compensation take more time to subside are present. Moreover, central banks may judge that the risks of doing too little to bring down inflation and having to step on the breaks even harder as a consequence, is something they are keen to avoid.

Advanced economy central banks have already taken their policy rates into levels that are restrictive, meaning that they would persistently bear down on demand if kept at these rates. In addition, we almost certainly see another round of rate hikes next month. A retreat of inflation and in particular core inflation is a necessary condition to see rate hikes ending, it is likely not a sufficient condition. Given tight labour markets, it is clear that central banks want to see convincing signs that the economy is turning down and subsequently that unemployment will turn up. Our base case is that these signs will be visible before long, but the risk is that they take longer to materialise, meaning that the peak in rates maybe somewhat higher than we forecast for both the Fed and the ECB. Having said that, we continue to see a pivot towards rate cuts later this year. The cumulative rate hikes over the last few months are still largely to hit the advanced economies. This will likely take shape over the next few months, with modest but protracted recession and higher unemployment. Second, we see inflation coming down more sharply than central banks expect. Core inflation ex shelter has already slowed markedly in monthly terms in the US, while real time data suggest shelter will tumble in coming months. The eurozone is further back in this process, but core inflation has mainly been drive up by energy-sensitive items and with energy inflation now collapsing, the core should follow with a lag. Finally, monetary policy will be at restrictive levels, and against the changing macro backdrop, the beginning of a normalisation process would be a reasonable step.