Global Monthly - What the banking turmoil means for the outlook

Much of the lingering concerns in the banking sector seem driven more by fear than fundamentals. However, market stress can become self-reinforcing, and even assuming financial conditions normalise, the turmoil could yet have a significant impact on lending to the real economy. The turmoil could mean an earlier end to rate hikes. But one way or another, the economy will need to experience some pain for inflation to fall sustainably back to target.

Global View: Some economic pain looks inevitable, even if the banking turmoil subsides

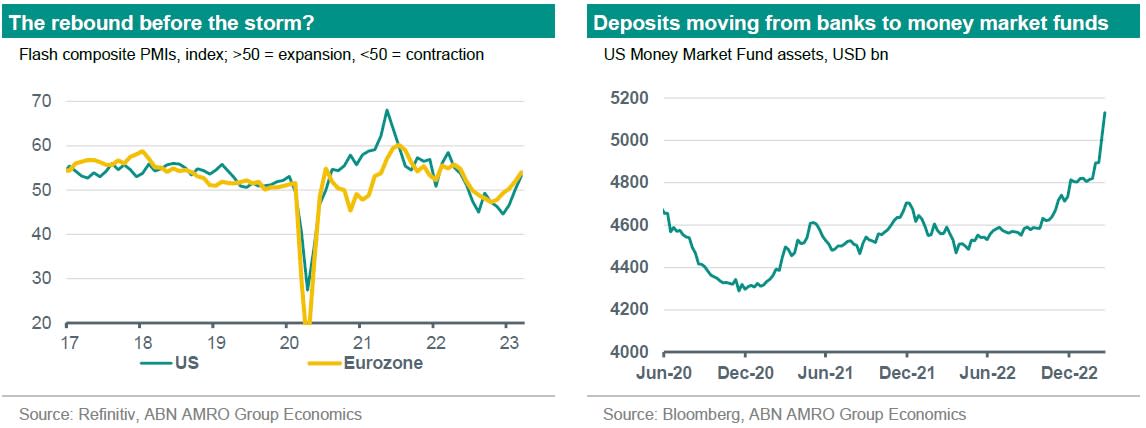

The global economy appears of late to ricochet from one crisis to the next. Just when the European energy crisis looked to be abating, financial markets have been thrown into renewed turmoil by a number of bank failures, and the fear of more to come. We ultimately expect that fear to subside, but in the interim, we could be in for some turbulence. In this month’s Global View, we pose a wide-ranging set of questions to our specialists – taking stock of the banking turmoil, pondering how events might unfold from here, and translating the impact of tighter financial conditions to the economy and monetary policy. Assuming the turmoil does subside, a key question for central bankers will be how much of a mark it leaves on financial conditions, and whether it reduces the need for further interest rate hikes. We think on balance that the Fed and ECB still have a bit further to go, but rate hikes could indeed end sooner if the impact on bank lending – and therefore growth and inflation – is more powerful than we assume. On the other hand, a more rapid easing in financial conditions could mean central banks have to go even further. One thing appears certain: last week’s bounce in the flash PMIs, suggesting a rebound in advanced economies, is unfortunately unsustainable. One way or another, economies will unfortunately need to experience some pain to bring inflation back to target, whether that is central bank-induced or otherwise.

Are we heading for a new banking crisis?

The banking sector has been the focus for financial markets since the failure of some regional US banks, as well as the take-over of Credit Suisse (CS) by UBS. The rise in bank worries resulted in a drop in bank share prices as well as bonds. This has raised the question of whether we are heading for a 2008-style global financial crisis. We do not think so, as we see the troubles on both sides of the Atlantic as idiosyncratic, while authorities and central banks have also acted forcefully.

Banks are much better capitalised than during the GFC 15 years ago (also something stressed by regulators on both sides of the Atlantic), which makes them better positioned to weather headwinds. Banks also have a lot of cash. This is reflected in the average CET1 ratio of 14.2%, and an average liquidity coverage ratio of 148% for the largest banks in the euro bond indices. The end of the negative interest rates era has also supported banks’ net interest income, which should be more than sufficient to compensate for any losses stemming from the weak economic outlook. In short, bank fundamentals have clearly improved. Working in the opposite direction, bank funding costs are set to rise due to recent developments (especially the cost of capital), which will weigh on bank earnings and might also result in banks further tightening lending conditions. But on balance, the banking sector looks sound. The lesson from recent developments has nevertheless clearly illustrated that confidence is key, and it is likely to take some time for confidence in the banking sector to be restored.

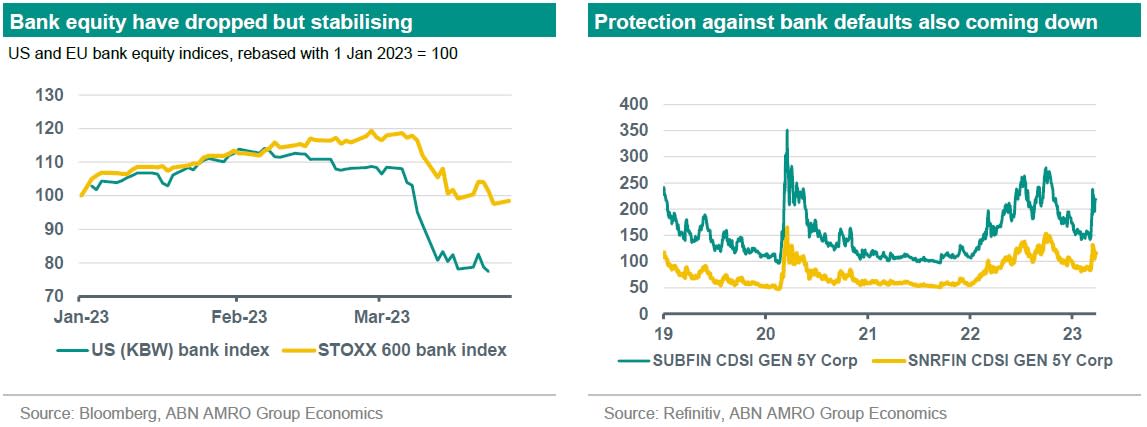

In recent days, bank equity and bond prices have stabilised somewhat, although markets have remained very volatile. Moreover, the costs of protection against bank defaults have risen strongly, although they have remained below levels seen during earlier times of stress. Having said that, the situation remains fragile.

Why is the banking stress idiosyncratic?

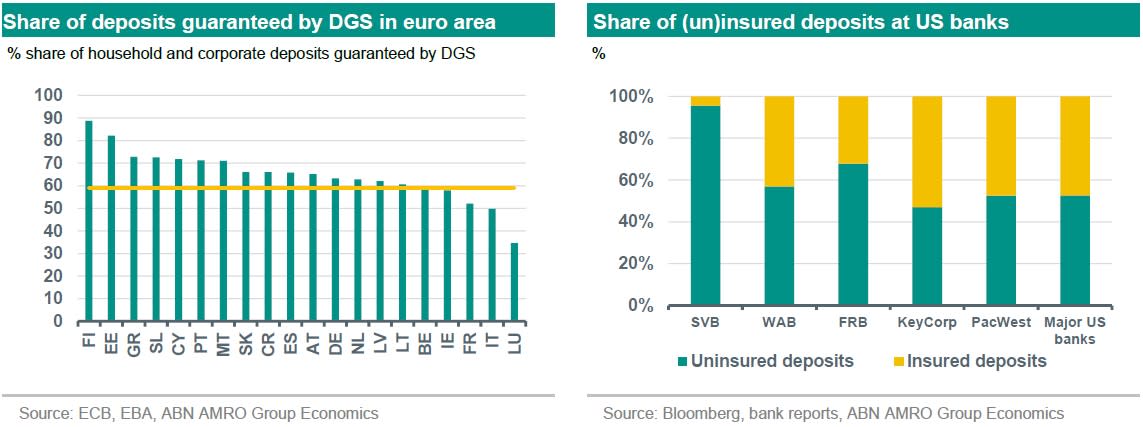

The problems with the US regional banks, and those of the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) especially, stemmed largely from the large share of customer deposits that were not protected by the US deposit guarantee scheme (DGS), which protects deposits up to USD250k. This made these banks highly vulnerable to a bank run when customers started doubting their viability. Meanwhile, SVB had not hedged the interest rate risk of its balance sheet, which meant that it would incur large unrealised losses on its investments following the rapid increase in market interest rates (mirroring aggressive policy tightening by the Fed). SVB was able to do this partly because in 2018 US lawmakers voted to reverse part of the Dodd-Frank Act for mid-size and regional banks.

Meanwhile, Credit Suisse had been one of the most beleaguered banks for some time, shrouded in negative headline news as well as doubts about the execution of its strategic review. The bank then almost completely lost market confidence after news about weaknesses in its controls over financial reporting, while the news that its largest shareholder would not be able to raise its equity stake did not help neither. As a result, customers withdrew large sums, culminating in a rescue by UBS.

The situation is different for other banks. For starters, the share of deposits at euro area banks that are guaranteed by the DGS is around 60%, much higher than SVB’s 4%. Other US regional banks also have a higher share of insured deposits, although some, such as First Republic Bank, still have a relatively large share of uninsured deposits. However, the US government has protected all uninsured deposits of the failed banks, which should also have restored some calm at other banks. Overall, we judge the risks of more bank runs as limited.

Another reason we think that a new banking crisis is unlikely is that most banks (unlike SVB) hedge their interest rate risk, only exposing their investments to market risks. A study by the ECB published in May 2022 () showed that euro area banks stepped up hedging activities in the past two years, limiting their interest rate exposure. Meanwhile, the ECB already conducted an exercise at the end of last year assessing the vulnerability of the euro area banking sector to a major flattening/steepening of the yield curve (see ). The stress test revealed that most banks were well positioned to cope with such a flattening of the yield curve. Perhaps more importantly, these studies show that the ECB is ‘on the case’ and aware of the risks that the current interest rate environment poses to banks. As a result, the central bank should also be well positioned to identify the banks at risk, telling them to act if needed.

Have markets entered calmer waters?

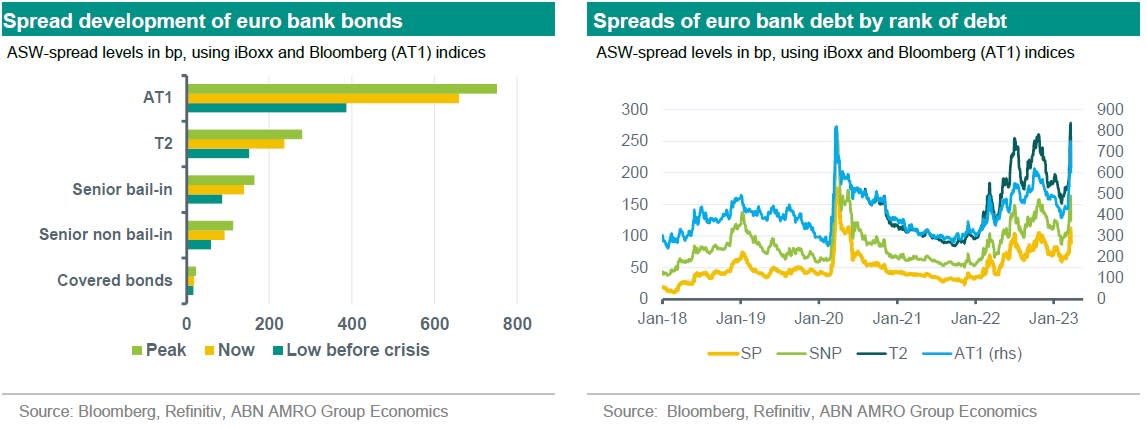

Well, only to a certain extent. Euro denominated bank bonds have recouped some of their losses, but spreads remain well above the lows reached earlier this year. The graph below left shows the peak, low, as well as the level of the index spreads by debt instrument in the past few weeks (with a higher level meaning a lower value of the bond). It reveals that the spread level of AT1s, the most sub-ordinated bank bonds, almost doubled compared to the lows of a few weeks ago. This was due to the treatment of AT1s of CS in the rescue of the bank by the Swiss authorities, which left AT1 bond holders worse off than CS shareholders (which is out of sync with the capital structure of banks). However, reassuring statements by EU and UK regulators that this would not happen in their jurisdictions resulted in a tightening of AT1 spreads, leaving them still 270bp above their low.

Overall, spreads of euro bank debt have tightened somewhat since the repricing following the flaring up of tensions in the banking sector, although they have far from fully recouped their losses. This reflects that weakness in sentiment towards the banking sector is ongoing, clearly indicating that the banking sector is not out of the woods yet. (Joost Beaumont)

How does the banking turmoil impact the growth outlook?

While financial markets have calmed somewhat, it is too early to tell which effects persist and which will fade, and at what point in time. One probable scenario is that the banking turmoil does not flare back up to the levels we saw over the past two weeks, but instead lingers on in the form of elevated tightness in the credit space for the foreseeable future.

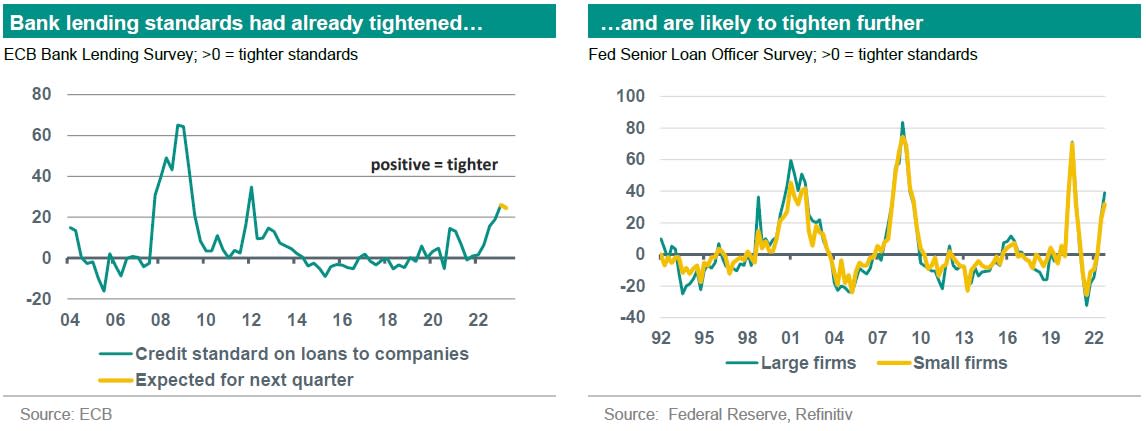

Multiple factors could contribute to tighter financial conditions going forward. It has become clear that a goldilocks scenario – with interest rates rising at the quickest pace in decades without any effect on financial stability or growth – now looks highly unlikely. We instead appear to be entering a more challenging phase, where uncertainty and fragile investor confidence leads to tighter financial conditions constraining lending, especially in more risky asset markets. The fact that the shock happened in banking also matters, as a repricing of risk and less confidence in the banking sector could lead to persistent elevated funding costs for banks which they then pass on to clients, either in the form of risk aversion by demanding higher credit standards, or in the form of higher interest rates to recoup elevated funding costs. Even before the turmoil broke out, Fed and ECB loan officer surveys suggested a considerable tightening in lending standards, and that is likely to continue.

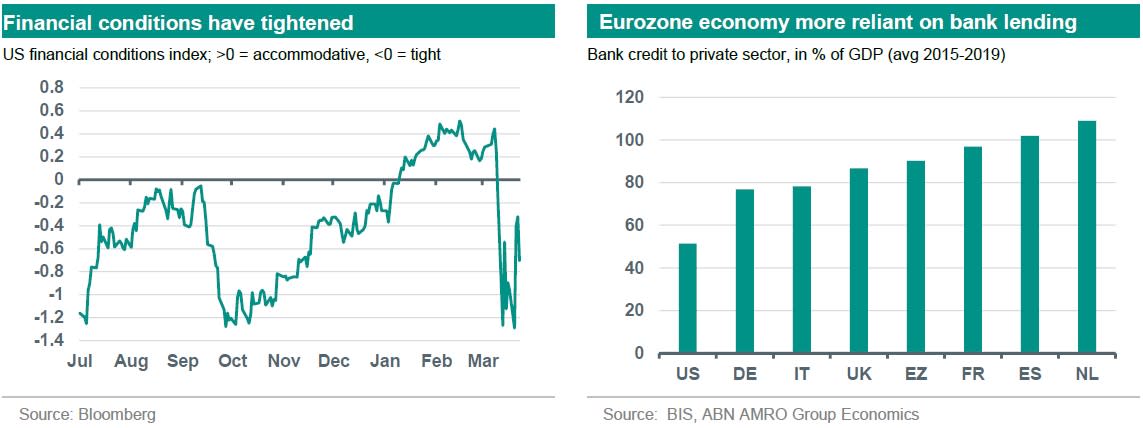

Should such a scenario play out, these factors are likely to further constrain (bank) lending to the real economy, above and beyond the impact interest rate rises were already having. Early signs of this effect are visible in financial conditions indices, and as Fed chair Powell noted in the March FOMC press conference, the impact on credit conditions could well be greater than aggregate indices suggest, with the hit to the real economy also correspondingly bigger. Tighter financing conditions do not evenly pass through to the economy. Interest rate sensitive and highly leveraged sectors such as real estate and construction are more at risk. Also, less consolidated sectors with a large share of SMEs, which typically are more reliant on bank funding, are also more exposed to the negative impact of tougher financing conditions.

Finally, it is worth noting two important differences between the situations of the US and the eurozone. Firstly, problems with and confidence in regional banks in the US seem at this point more widespread than the banking issues in the eurozone, which so far have been contained to the isolated (and highly idiosyncratic) case of Credit Suisse. This means the possible effects on bank lending are likely greater in the US. Secondly – and a counter-point to this – the eurozone is much more dependent on bank funding than the US (see chart on next page). Turmoil on a similar scale in the eurozone banking sector would therefore have bigger repercussions here. (Jan-Paul van de Kerke)

Will the banking turmoil throw rate hikes off course?

So far, central banks have continued to raise interest rates, despite the risk the recent turmoil poses to the real economy. This is conditioned on the crucial assumption that the turmoil can be dealt with via emergency liquidity (such as the Fed’s offer of funds secured against Treasury bonds valued at par) or regulatory measures (such as the implicit extension of deposit guarantees), and that the turmoil will not evolve into a broader crisis. Central banks still have a job to do to bring inflation back down to target, and so as far as possible they would prefer to keep raising interest rates to finish that job than to allow the focus of this to be muddied by financial stability concerns. There is also a danger that if central banks were to pause rate hikes on financial stability concerns, that this would have a counterproductive effect by suggesting to markets that there is a bigger problem in the banking sector than appears.

With that said, central banks cannot ignore the tightening of financial conditions that has resulted from the stress in the banking sector, because to some degree, this does part of the work for central banks by dampening lending to the real economy, reducing aggregate demand, and in turn inflationary pressure. For this reason, we forecast only one further rate hike by the Fed – despite the recent bad news on inflation – while for the ECB, we see the risk to our forecast peak in the deposit rate (3.75%) as tilted to the downside.

But there is significant uncertainty over the degree to which financial conditions will stay tight. Since the rescue of Credit Suisse, financial conditions indices have retraced much of the tightening that occurred since the turmoil broke out. As mentioned above, it is likely that such indices understate the true extent of the tightening in financial conditions, given that they don’t capture the likely tightening in lending standards, and this is something we will not have a good handle on for some months potentially. Should the tightening in financial conditions prove to be greater than estimated, central banks are likely to pause rate hikes sooner and could even embark on earlier rate cuts. On the other hand, if financial conditions ease more rapidly from the turmoil, this could be a reason for central banks to hike by even more than we currently forecast, and for rates to stay higher for longer. Indeed, this uncertainty led the ECB to explicitly drop guidance for where it expects interest rates to go, while the Fed – though retaining a tightening bias – significantly softened this bias, remarking in its policy statement only that further rate hikes ‘may’ be appropriate. (Bill Diviney)

Could a situation arise where the authorities are unable to provide an adequate fix?

Events over the past two weeks have demonstrated that the banking sector reforms that were introduced in response to the Global Financial Crisis were insufficient to prevent the demise (or near-demise) of three banks in the US and one systemically important financial institution (SIFI) in Europe. These banks had what one might consider an adequate first line of defence, with robust solvency ratios and yet, concerns about liquidity emerged which then forced the authorities to provide a de facto blanket guarantee on all deposits (in the US at least), and to put in place aggressive liquidity measures to restore confidence in the sector. Even that was not enough. In the end, the UK authorities had to step in to facilitate the takeover of the UK arm of SVB by HSBC, and the Swiss authorities engineered the takeover of Credit Suisse by its larger rival, UBS. These stress events have also resulted in tighter conditions for banks.

The current banking sector stress episode followed a significant dislocation in UK financial markets in September last year, where a ‘doom-loop’ developed as losses from higher sovereign yields in the pension industry triggered forced selling resulting in further losses. The Bank of England had to step in as market maker of last resort in gilts and crucially, from a monetary policy perspective, the central bank had to delay the start of its pre-announced quantitative tightening programme because of worries related to financial stability. Are these episodes together a signal of more trouble to come? And are there circumstances under which tremors such as these can morph into a crisis? Here, it is important to recognise that:

banks and other firms in the financial sector are businesses that take risks, and risks that go wrong can result in failure. This implies that the financial sector will continue to suffer such dislocations in future

not all financial sector stress episodes result in a global financial crisis

stress in the financial sector can take different forms. It could emerge from within the sector or from outside

the authorities have multiple tools at their disposal, and policymakers will play a key role in ensuring that a financial sector stress does not morph into an economic crisis

Events over the past six months have demonstrated that firms in the financial sector will continue to run into trouble, but that these dislocations are manageable as long as the authorities are able and willing to intervene. That remains our central view, but there are risks to that view.

Let’s start with the economic backdrop. Central banks have embarked on the most aggressive monetary tightening in decades. Economic activity has slowed, but inflation remains stubbornly high. The supply shocks that have created the divergence is different from the more common demand shocks, where growth and inflation tend to move in the same direction. This divergence is both unusual and uncomfortable for monetary policy.

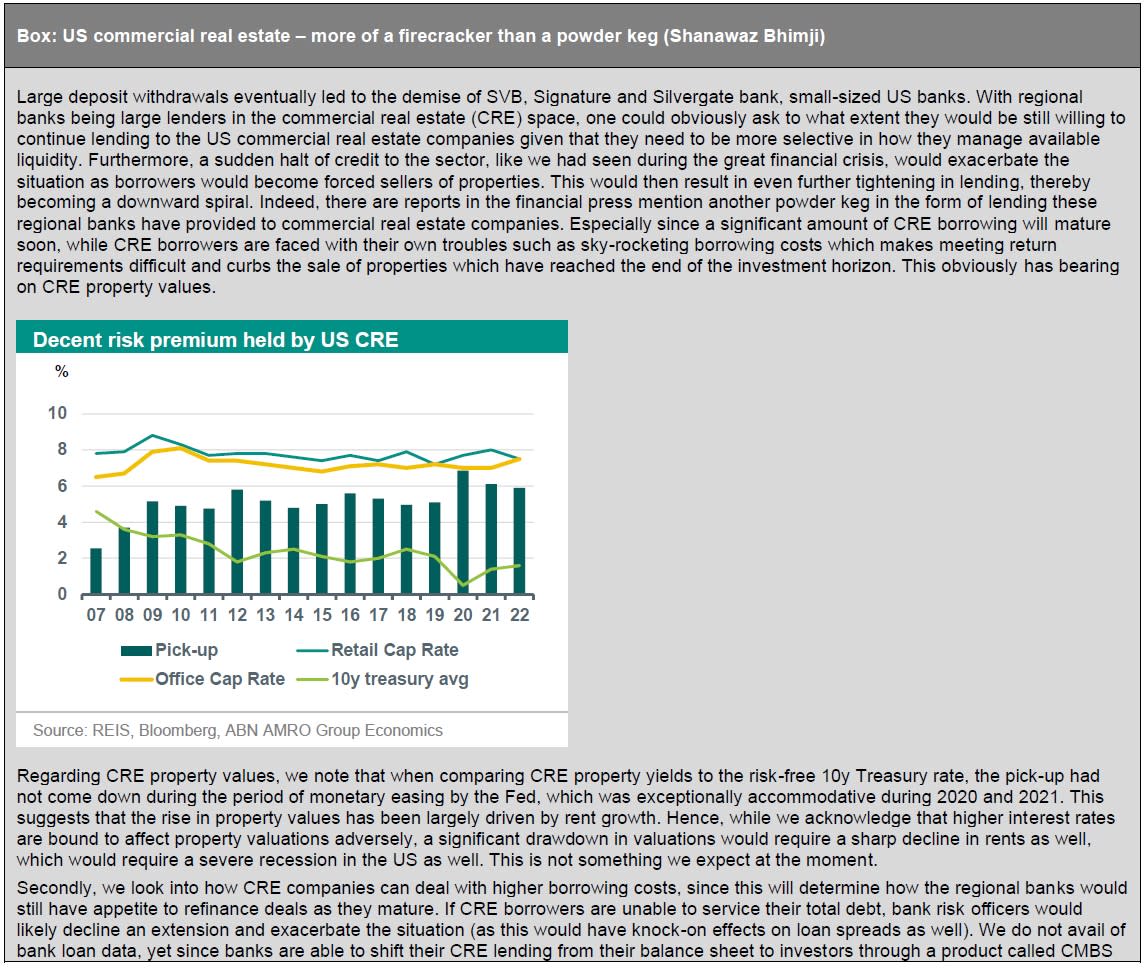

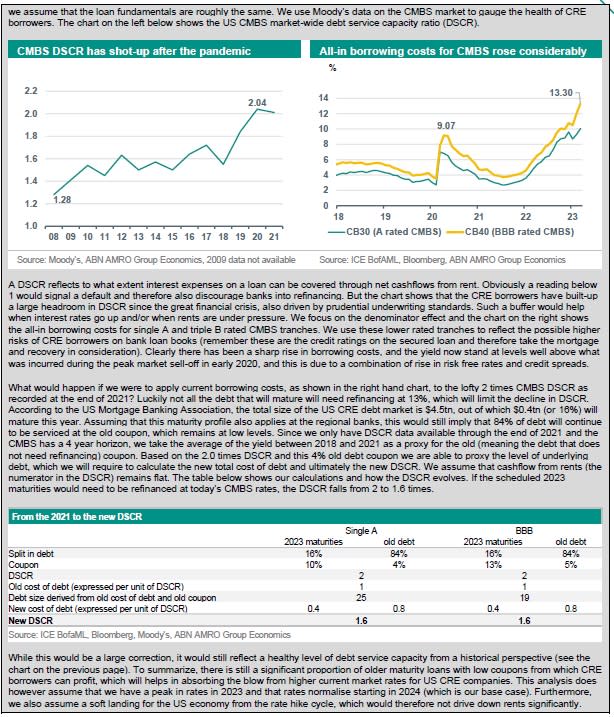

What has been more usual is the response of asset prices to the monetary tightening cycle. House prices are falling in many advanced economies, and the commercial real estate sector is under pressure because of new working patterns in response to the pandemic as well as higher borrowing costs. US banks are exposed to an unrealised loss of USD620bn on securities held either for sale or held to maturity.

These recent events demonstrate that the first line of a bank’s defence, namely its capital and liquidity buffers, is vulnerable to bank runs that result from a loss of confidence. Could circumstances under this backdrop where the second line of defence is also breached? In our view, yes: a plausible scenario could be a wage-price spiral triggered, say, by a government that is tempted to ‘fix’ the ongoing cost-of-living crisis. Another possible scenario is stubbornly high inflation. The central bank would need to tighten monetary policy to anchor inflation expectations. Asset prices would fall as a result. A scenario such as this could also result in financial markets questioning the government’s solvency and that in turn could widen sovereign risk premiums, resulting in higher borrowing costs for the government and a loss in asset prices more generally. (Amit Kara)