The Netherlands - Domestic strength to face turbulent times

The economy has showed robust growth over the past year; growth is expected to continue in 2025. But with a precarious external environment, growth will be domestically driven. Unemployment will increase slightly, but the tight labour market remains a constraining factor. Inflation still at 2.5% in 2026, higher than the eurozone, creating risks to competitiveness.

Growth robust after period of stagnation, but tariffs cloud the outlook

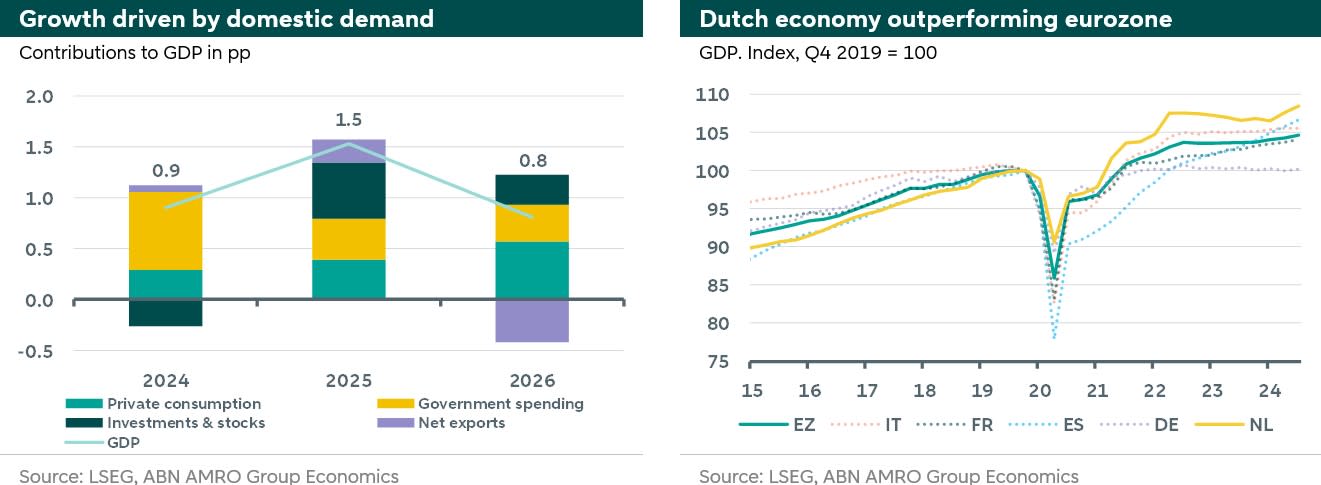

In 2024, the economy has performed robustly. While growth in Q1 was still meagre, the second and third quarters showed solid growth with GDP expanding by 1.1% and 0.8% q/q respectively. The economy is clearly recovering from high inflation induced stagnation in 2022/23. Since then, the Netherlands has outperformed the eurozone aggregate. Looking ahead, risks on the external side are tilted to the downside. Yes, external demand benefits from the continued eurozone recovery in the near term, but an extended stagnation in main trading partner Germany and later on potential Trump tariffs cloud the outlook. As a result, growth will be domestically driven. We expect annual growth to average 0.9% this year, and 1.5% next year, before slowing to 0.8% in 2026 following the introduction of US import tariffs.

Domestic demand to drive growth …

In the Netherlands, a trade-oriented economy, growth typically originates externally. An increase in exports gradually benefits households and boosts domestic demand. In the coming two years, the reverse will take place. Due to drags from the external side, it is mainly domestic demand that will drive growth. With wage growth remaining at historic highs (6.7% y/y in October) and expected to continue outpacing inflation in the coming quarters, households are benefiting from rising real incomes and supportive government measures. In the first half of 2024 the spending impulse from this was delayed, as households prioritized saving and deleveraging over consuming. Going forward, as real income growth continues, consumer confidence improves further, and mortgage lending (a leading indicator for durable goods spending) picks up, we expect household spending to continue expanding for the remainder of 2024 and into 2025. High savings and households making additional downpayments on their have been a silver lining. Households’ balance sheets, in aggregate, have improved, providing a robust starting point for the coming years.

The economy also benefits from the expansive fiscal stance of the Dutch government. In other large eurozone economies the fiscal stance in 2025 is broadly neutral or even significantly contractionary. The Netherlands stands out in that regard. Indeed, in 2024 government consumption already added a forecasted 0.8 pp to growth, and also in 2025 and 2026 this contribution is expected to be sizeable. In the budget we see that spending is mostly concentrated on healthcare, public administration and refugee shelter. In their policy plans, the new Schoof cabinet has shifted spending away from longer term investments towards more short-term goals, such as boosting purchasing power. This will provide an impulse to private consumption and investment in 2025. Still, just as in past years, the constraint of the policy agenda lies in the execution. Given the tight labour market, the risk of underspending remains high.

Investment, the final component of domestic demand, performed solidly throughout the year. A bit unexpected given high interest rates, (geo)political uncertainty, the underperforming German economy, and the tight labour market. The government likely made a substantial contribution to overall investment growth, while private investment growth was somewhat lower. The lagged pass-through of rate cuts will provide support, but the impulse might take longer to materialize, since rate-sensitive sectors such as construction and manufacturing remain among the most constrained sectors by internal bottlenecks, like labour market tightness and grid congestion.

… while risks loom on the external front

Due to the open nature of the Dutch economy, changes affecting global trade affect the Dutch economy relatively more. In the coming quarters, we expect foreign demand to pick up, in line with eurozone growth continuing. Given our Trump tariffs scenario, assuming a gradual stepping up of US tariffs, Dutch exports to the US and in general are impacted negatively from Q3-25 onwards. Before that, we may actually see an upside to growth: US companies frontloading imports in anticipation of the tariffs boosting Dutch exports. The Netherlands will see a stronger drag from US tariffs compared to the broader eurozone, with the growth effect primarily visible in 2026. Closer to home, weakness in Germany – the Netherlands’ main trading partner – has kept a lid on export growth. Although the Netherlands' dependence on Germany has been falling, with the of Dutch goods exports to Germany decreasing since 2012, weak growth prospects in Germany continue to impact demand for Dutch exports.

Tight labour market puts potential growth under pressure

Over the past years, the employed workforce has grown steadily, but not fast enough to meet all the labour demand. The number of vacancies still surpasses the number of unemployed, and businesses still report a lack of personnel as the main constraining factor. Labour market tightness is here to stay in the coming years, as the pool of people that can still enter the workforce is drying up and the number of unemployed is low. Additionally, the growth of the labour supply – a source of economic growth in the past – is slowing in the coming two years and set to turn negative from 2027 onwards. Together with a slowing of productivity growth, an economy at capacity constraints, and limited scope to increase participation or the number of hours worked, potential GDP growth is facing downward pressure. As a result, labour shortages will remain a large bottleneck for the Dutch economy.

Inflation diverges from eurozone aggregates, creating risks to competitiveness

We expect that inflation in the Netherlands will remain above the ECB’s 2% target in the coming years, with an average of 3.3% this year, decreasing to 3.1% next year, and reaching 2.5% in 2026. Dutch inflation remains a story of services, driven by still high wage growth and housing rent increases. Food prices have also risen due to higher levies on tobacco and drinks. On the other hand, price pressures from industrial goods and energy are decreasing. Going forward we expect Dutch inflation to decline, but to stay above eurozone inflation for a number of reasons. First, higher inflation peak in 2022 leads to a larger catch-up in wages. Indeed, wage growth in the Netherlands is higher than the eurozone average, also due to the tight labour market. Second, the fiscal stance of the government is at odds with monetary tightening. Third, tax increases, for instance on hotels and leisure and fuel excise levies in 2026, provide an upward impact on inflation. The long tail of Dutch inflation creates risks for Dutch competitiveness.

Dutch coalition increasingly unstable, possibly delaying reforms

Since the Schoof cabinet – consisting of PVV (far-right), VVD (liberal centre-right) and newcomers BBB (right) and NSC (centre-right) – started in July, it has been troubled by internal discussions with most recently two departures of NSC cabinet members. While a lot remains unclear about the future, or a possible fall, of the coalition, it is likely that these troubles impact the ability of the government to adequately address the many bottlenecks faced by the Dutch economy. Indeed, plans to solve the nitrogen emission crisis lack concreteness, and so do the plans to increase housing supply. Together with other bottlenecks, these constraints are expected to affect the economy going forward. .