Global Monthly - Six themes to watch over the summer

Despite the rollercoaster ride in between, the landing zone for tariffs is looking remarkably close to our expectations last November. Trade deals are likely to be announced over the coming weeks, and even if they aren’t, we will probably see deadlines pushed back. Growth is still expected to slow near-term, but downside risks have been reduced, while a re-escalation is likely to prove short-lived. Further out, the US economy is expected to weaken, while eurozone growth is expected to pickup, driven by higher German fiscal spending. We preview these and other themes to watch over the summer. Spotlight: In this Sustainability special, we lay out the macro-economic impact of Net Zero and Delayed Transition scenarios.

Global View: Last month reminded us that tariffs aren’t the only driver in town of the outlook

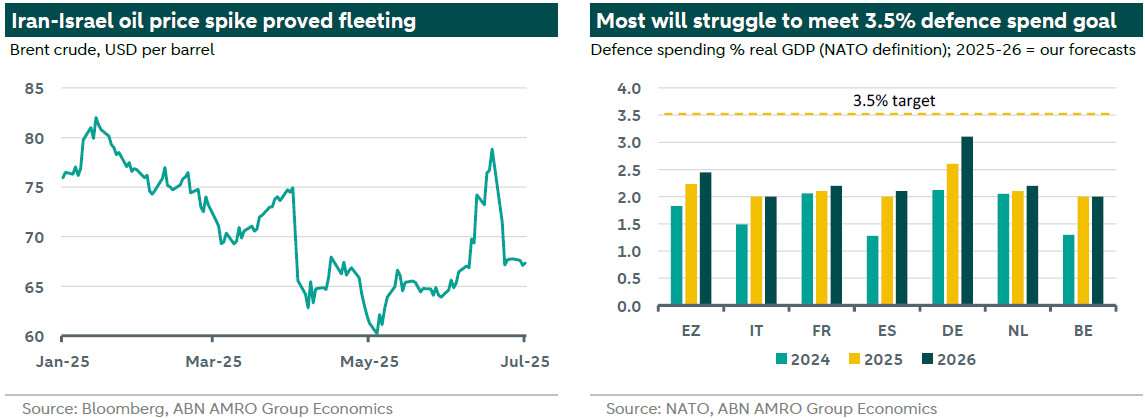

June was the first month this year when the economic news cycle wasn’t dominated by tariffs. Instead, the conflict between Israel and Iran reminded us how vulnerable the world is to sudden geopolitical shocks, even if this particular shock proved to be fleeting. The news cycle was also dominated by the NATO Summit. Our take was that although the new 3.5% of GDP core defence spending goal looks unrealistic for many countries, it is still likely to spur significant rises in spending by European countries over the coming years. If the past month was lacking tariff-related news, we may not be so lucky over the coming months. The US’s 9 July deadline for trade deals to avert another jump in tariff rates is now rapidly approaching. EU negotiators are in Washington as we publish, and the White House’s National Economic Council director has suggested a number of deals will be announced after 4 July. Even if a US-EU deal is not done, we expect either the deadline to be pushed back, or that any re-escalation will prove short-lived. To be clear, US tariffs are still expected to weigh significantly on growth in the near-term. But as described last month, the downside risks are considerably lower. Meanwhile for Europe, the upside risks to medium term growth have increased on the back of the German frontloading of spending. This month, we preview these and other key themes to watch over the summer. As well as looking forward, we also look back and take stock of how the year has progressed so far, with a critical eye on where our calls have gone well, but also not so well.

Lookback: How has 2025 progressed so far?

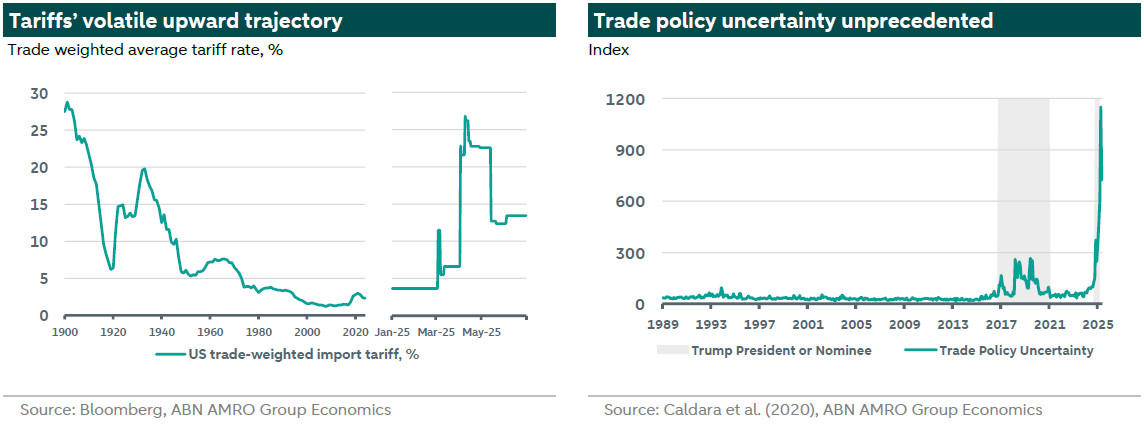

Back in November – in the aftermath of Trump’s re-election – our Global Outlook declared 2025 the Year of the Tariff. Events have certainly not disappointed, and if anything, US import tariffs came more quickly and with more bombast than expected: we thought tariffs would start in Q2 with US imports from China and in Q3 for imports from the rest of the world. In both cases tariffs started one quarter sooner, reaching their peak around Liberation Day on 2 April. In terms of tariff rates, we still do not know the final landing point, as this is still subject to negotiation, but it is likely to be remarkably close to our base case from November: we now think a 10% universal tariff (with exemptions) will stay in place for most countries – consistent with our base case of a 5pp rise in the effective tariff rate after exemptions are taken into account – with a ±40% effective tariff for China (our expectation: 45%). So far, so good.

What we did not predict was the rollercoaster ride getting to these likely landing zones, and the economically-damaging uncertainty this has caused. For a brief time, tariffs on goods from China were raised to 145%, which a combination of corporate lobbying and financial market pressure ultimately put an end to. We also expected more growth-supportive measures in the US, with more emphasis on deregulation and tax cuts, than ultimately materialised. Tax cuts are now imminent in the form of the Big Beautiful Bill, but unlikely to offer much support. On the flipside, and closer to home here in Europe, while we flagged the risk of a game-changing shift in Germany’s debt brake as well as more broadly European defence spending, the scale and speed of these shifts has also surprised, leading us to raise our eurozone growth expectations for 2026 in particular.

How did our forecasts perform on the back of all of this? Our growth forecast for the eurozone in 2025 is now fairly close to where it was in November, at 1.1% vs 1.2%, but is substantially higher now in 2026 due to higher expected fiscal spending, at 1.1% vs 0.8% previously. In contrast, in the US, growth is notably weaker due to the lack of compensating growth-stimulating policies to offset the tariff shock, but also the economic damage wrought by policy uncertainty from the erratic US administration. Growth in 2025, for instance, is now projected at 1.3%, down from 2% in November. With regards to inflation, we have yet to see significant upward pressure from tariffs in the US, though the risks remain significant (see here and below), but in the eurozone, inflation is set to fall well below the ECB’s target over the coming year – in line with our November forecast, but in stark contrast to the ECB staff (and consensus) projections at the time.

What did all of this mean for central banks and financial markets?

So far, the ECB has lowered rates broadly in line with expectations late last year, though it has signalled it is coming to the end of rate cuts somewhat sooner than we projected then (see Eurozone). This is driven chiefly by upside risks to growth in 2026 from the reform of the German debt brake, and higher defence spending. Meanwhile, the Fed paused interest rate cuts sooner than we expected. Back in November, we thought the FOMC would shift to a quarterly rate cut pace, but the scale of tariff threats and the rise in inflation expectations led to an earlier hawkish shift. This has been reflected in our base-case since February, when we changed our forecast to no cuts for the remainder of the year, based on a forward-looking Fed that’s afraid of inflation de-anchoring. More hawkish central bank expectations, combined with a jump in US term premium driven by fiscal worries, led to rises in bond yields, in contrast to the falls that we projected in November.

It was in FX markets where dynamics really surprised. We expected the combo of more elevated Fed rates and lower ECB rates to drive EUR/USD lower, as it typically would. What we did not foresee was that the erratic policymaking of the Trump administration would so rapidly erode investor preference for US assets. Negative investor sentiment towards the US ultimately overwhelmed the widening in short-term rate differentials, driving EUR/USD higher. This was spurred by Germany’s game-changing debt brake reforms, which supported the euro. With the US Congress now seemingly on the verge of passing Trump’s Big Beautiful Bill, might the dollar sell-off now have further to run? We expect further rises in EUR/USD over the coming year, as shifting investor preferences alongside an unfavourable growth-inflation mix in the US, and the administration's domestic policies, put further downward pressure on the dollar. While vulnerable to a near-term correction, we ultimately expect EUR/USD to rise to 1.25 by end 2026.

Six themes to watch over the summer

With our customary summer break about to start (we resume publishing in late August), the Macro Research team previews six key themes to watch over the coming months.

1. Will trade deals be sealed in time? Could the trade war re-escalate? Is there room for positive surprises?

Even if deals aren’t done by the 9 July deadline, any escalation is likely to prove short-lived.

The US and its key trade partners are currently locked in negotiations to avoid even higher tariffs, which are officially due to kick in on 9 July. For instance, if the EU does not agree to a trade deal (or at least an interim ‘framework’ as with the UK and China recently), it is due to be hit with a 20% – potentially 50% – blanket tariff instead of the 10% tariff currently in place. Should such tariff rates be imposed for a prolonged period, they would be far more damaging than the existing tariffs in place, leading to a sharp fall in exports to the US and risking a eurozone recession. Other countries face similar cliff-edges on 9 July, while China could in theory see a return to higher tariffs if trade tensions were to re-escalate (see China for more). We continue to think a US-EU trade deal is likely to leave the 10% universal tariff in place, with lower tariff quotas for categories hit with higher tariffs such as cars, similar to the deal the US has struck with the UK. This scenario underpins our growth forecasts. EU and US officials have signalled in recent days that they will be able to reach a framework agreement by the deadline.

What if they don’t? Most likely is that the US simply extends the deadline. But it would also not be surprising if things re-escalate and the US imposes higher tariffs, potentially with EU retaliation. Should this happen, the China episode suggests this would be unlikely to last for very long. An escalation would also be damaging to the US, and the past few months has shown us that the Trump administration has limits to how far it is willing to go with its combative trade policy. Given this, although our base case for tariffs is still expected to be damaging, we think the growth impact from a renewed escalation would likely be short-lived.

There are other uncertainties aside from the deals themselves. The US has opened investigations into other product categories that have yet to see tariffs imposed, for instance on pharmaceuticals. This is important for the EU, given that pharma makes up ¼ of EU exports to the US. On the positive side, the US has signalled that it may remove the 20% fentanyl-related tariffs imposed on Chinese imports, which unlike other China tariffs cover all imports from China. So, the risks to the trade policy outlook are not only to the downside. (Bill Diviney, Rogier Quaedvlieg, Arjen van Dijkhuizen)

2. How far will exports to the US fall after the tariff shock? What other spillover effects can we expect in Europe?

Exports to the US are likely to fall even further in the near-term. European industry also faces a weaker US consumer, a stronger euro, and other spillovers.

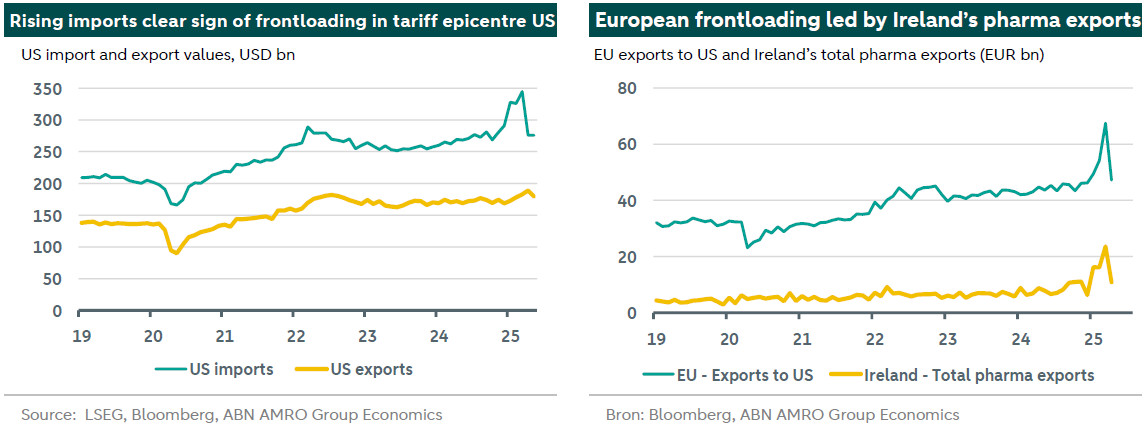

In the first quarter of this year, most countries saw a massive jump in exports to the US in the run-up to higher import tariffs (see our Global Trade Watch, Frontloading precedes tariff shock for more background). These signs were particularly strong in tariff epicenter US, where a surge in imports (see chart) led to a deeply negative contribution from net exports to Q1 GDP, with overall GDP contracting. But we also saw evidence of this in China and the eurozone. In China, frontloading was particularly visible in exports to ASEAN, suggesting that exporters prepared early for trade circumvention routes to deal with higher US tariffs. In Europe, we saw a sharp rise of exports to the US in Q1, particularly in March. This benefited eurozone GDP growth in Q1, led by Irish exports of pharmaceuticals (see chart).

Recent data suggest we can expect the positive effects of trade frontloading seen in Q1 to unwind in Q2. US imports have fallen sharply back again in April, stabilising in May. US GDP figures for Q2 will therefore again be distorted, but this time to the upside, with the Atlanta Fed nowcast currently standing at 2.9%. Europe’s exports to the US (and Ireland’s overall pharma exports) also dropped back to pre-frontloading levels in April, and will likely fall further in May. We have therefore pencilled in a -0.2% contraction in GDP for the eurozone in Q2 (see Eurozone for more). In contrast, China’s overall exports held up well in April and May, in line with our view that the direct export shock to the US would be offset by trade circumvention (e.g. by rerouting through ASEAN) and by export diversification to other destinations than the US, including the EU (see China for more).

Looking beyond the effects of trade frontloading, and the unwinding thereof, the eurozone will face a lasting shock to exports from US tariffs, and will also be impacted by other spillovers from changes in the global trade landscape following the radical shift in US trade policies. Higher general US tariffs on the EU, coupled with product-specific Section 232 tariffs (e.g. on cars, steel/aluminium etc.), are likely to keep a lid on exports to the US over the medium term. EU exports to the US will also be hit by a likely softening of consumer demand in the US, and by further euro appreciation versus the US dollar. EUR/USD rose from 1.04 per end-2024 to currently 1.18, and we expect a further appreciation to 1.25 by end-2026. More indirectly, eurozone exports will be affected by the expected slowdown in global growth and trade stemming from US tariff policies.

Another type of spillover stems from trade rerouting and possible dumping. As noted above, China is looking for alternative destinations to offset the hit to exports stemming from higher US tariffs. In a recent report from an EU import surveillance task force (see ), a sharp rise in imports from China for product groups like machinery and textile is being reported, as well as a general steep rise in steel imports following the increase of US tariffs on steel and aluminium to 50% (see ). Finally, Europe may also hit by disturbances in global trade flows stemming from US tariff policies which are leading to new bottlenecks in global shipping, as signalled by reports of congestion in European ports (see ) and rising container tariffs for shipping from Shanghai to Rotterdam. (Arjen van Dijkhuizen & Bill Diviney)

3. How quickly will Germany deploy its fiscal bazooka? Can other eurozone countries ramp up defence spending as quickly?

Germany to frontload spending; other eurozone countries will struggle due to fiscal constraints and lack of political will.

As discussed in our lookback, one of the surprises in 2025 so far has been the scale and speed of Germany’s fiscal transformation. Following decades of prudence, incoming Chancellor Merz (CDU) tore up the rule book and declared he would do ‘whatever it takes’ to preserve ‘freedom and peace on our continent’. By doing so he delivered on one of the main promises in the coalition agreement between the CDU and the SPD. The most important changes to Germany’s debt brake were to remove the cap on all defence spending above 1.5% of GDP, and the new EUR500bn infrastructure fund. The budget announcement last week suggests much of the rise in spending is going to be frontloaded, with an extra EUR22bn earmarked for infrastructure this year already (0.5% of GDP), while defence spending is to rise by cEUR10bn (0.2% of GDP) compared with 2024. The speed of this spending increase is remarkable considering we are already halfway through 2025, and it points to a government that is determined to make a clean break with the past. Naturally there are question marks over the feasibility of this, but there are indications that in infrastructure, there are major projects that were ready to go at the time of the fall of the German government last year, for instance to revive Germany’s decrepit railway infrastructure (see ). With regards defence spending, as we have previously argued, much of the initial rise in spending is likely to ‘leak’ out in the form of higher imports, limiting the initial growth impact. However, we expect the growth impulse from this to become bigger as we move into 2026 and as domestic industry increasingly re-orients away from the ailing car sector and towards the booming defence sector.

The outlook is less rosy for the rest of the eurozone. Most countries are much more fiscally constrained than Germany, with the French government still vulnerable to imminent collapse due to its contentious efforts to bring down the deficit, while others like Italy are unable to run large deficits due to the existing high debt burden. Still others, such as Spain – which controversially sought an exemption to the new NATO 5% defence spending target – lack the political will to spend, with voters seemingly less concerned about defence than those closer to Russia’s borders (see here). Given all of this, we expect much more modest increases in spending in other eurozone countries, and those that do happen (for instance Spain and Italy have promised to raise defence spending to 2% of GDP already this year) are likely to be on the back of reclassifying existing government spending rather than genuinely new money going into the economy. With that said, Germany’s fiscal bazooka is likely to have spillover effects to other eurozone countries, particularly those with more developed defence industries, such as Italy and France. All told, we significantly raised our growth forecasts for Germany for Q4 2025 and 2026 (for 2026, our annual average growth forecast rises to 1.4% in 2026 from 1% previously), with a more modest rise in our eurozone growth forecast (up to 1.1% from 1%). (Bill Diviney & Jan-Paul van de Kerke)

4. Will we finally see inflation in the US picking up over the summer?

Probably.

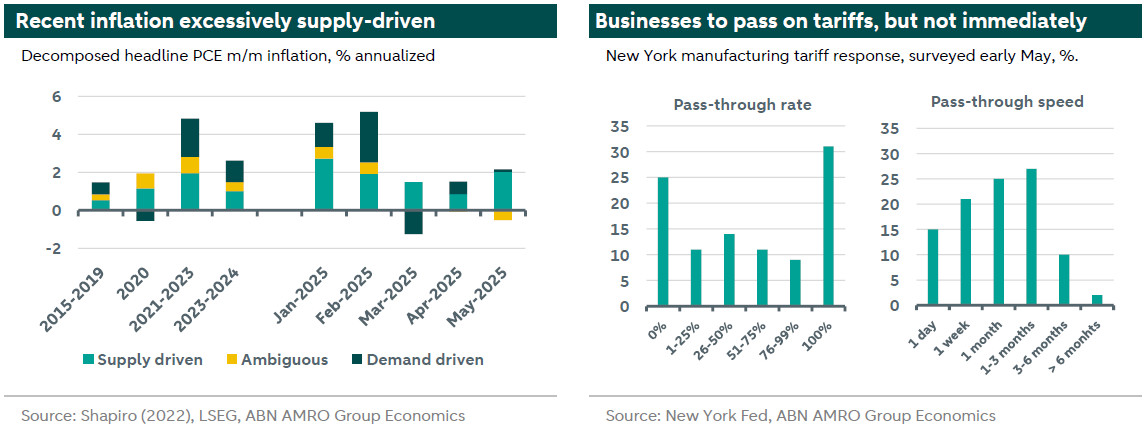

PCE inflation throughout this year, especially since March – when widespread new tariffs first hit – has been supply driven. Broadly speaking, the BEA’s consumption data allows one to see whether unexpected changes in price are associated with higher consumption (demand driven) or lower consumption (supply driven). Recent data has been entirely consistent with price pressures from the trade war, not from demand. In fact, consumer spending was very weak, particularly on services, coinciding with poor consumer sentiment in response to the uncertainty stemming from the Trump administration’s policy. This is further corroborated by the latest revision of the Q1 GDP figure, which showed the weakest quarterly consumption growth since the pandemic. Demand driven inflation has been effectively zero in the past three months, keeping a lid on overall inflation.

Still, the extent of pass-through from tariffs into prices has been limited. We’ve recently estimated ‘excess inflation’ in the second-decimal range, much less than the 0.9 pp implied by our models based on current policy. Recent survey evidence from the New York Fed provides a partial answer as to why. It shows that three quarters of manufacturing companies aim to pass on tariffs to consumers, with more than 30% wanting full pass-through. The timeline shows that some companies do it quickly, with about a third of the firms doing it within a week, and another quarter within a month. Still, with most tariffs being imposed at the start of April, there’s a significant group of firms where prices in May are not expected to show serious signs of tariff yet. The survey indicates that nearly 90% of firms should have passed through tariffs within 1-3 months, explaining the fact that the FOMC places large weight on the inflation readings over the summer.

There are many reasons why inflation may ultimately not materialize to the extent, or with the speed, that our models predict. First and foremost is that the levels of tariffs we see now have no precent in modern economic history, meaning that there is substantial uncertainty in the forecasts themselves. Indeed, firms may react differently to this level of tariffs. They may absorb some of the costs, they may try harder to avoid the tariffs altogether, or they may even spread out the price hikes across regions other than the US. Maybe, despite their reported assessment of when to pass on the costs, they are still awaiting clarity on tariff policy before raising prices, in which case it might take even longer than this summer.

Our view remains that inflation will start to pick up, preventing the Fed from easing in September. There is however just as much uncertainty over the extent to which weaker demand-side inflationary pressures persist. There is a scenario where the lack thereof pushes baseline inflation down sufficiently far that even with tariff-induced (supply driven) inflation, the overall inflation level remains consistent with the 2% target. This is likely the scenario that FOMC members that pencilled in two cuts this year have in mind. It is by no means a good scenario given that it implies weaker growth, and certainly not the soft-landing that seemed all but reached at the end of last year. (Rogier Quaedvlieg)

5. Will we see another ‘Sell USA’ episode?

While exact triggers are hard to pin down, we’re likely to be in for a bumpy ride.

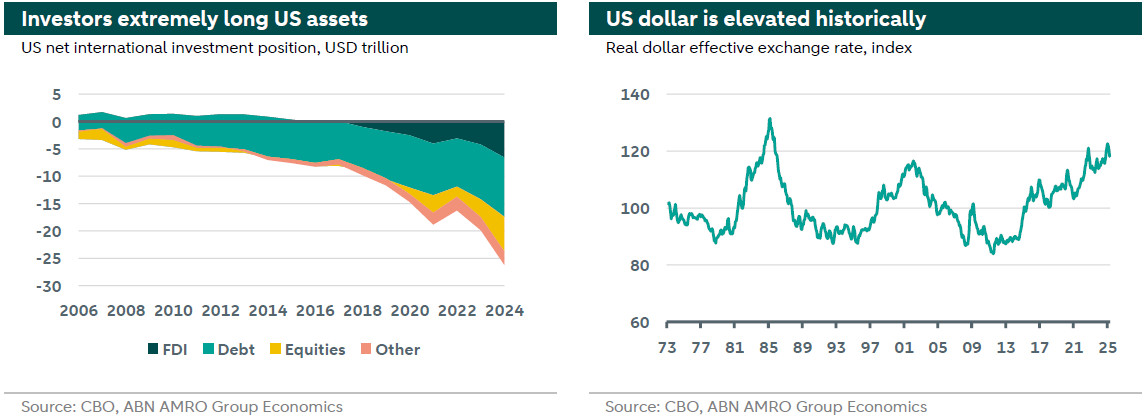

One of the big market themes of this year has been a possible shift by investors away from US assets. At the end of last year, investors looked to be extremely long US assets, looking at the net international investment position of the US (see chart below on the left). This has gone hand-in-hand with the US dollar rising to extremely high levels from a historical perspective (see chart below on the right). US exceptionalism has had a number of different sources. First, the US economy has generally performed relatively well over the last few years and real interest rates are high compared to other developed economies. Second, the US has a thriving tech sector and is well placed to benefit from a transformative impact of AI as a general purpose technology. Third, the US has continued to benefit from having the world’s reserve currency, with deep and liquid capital markets. This has allowed the government to issue debt at lower interest rates than it would otherwise.

The mood on US assets has changed over the last few months, to a large extent reflecting concerns about the new US administration’s policies, the unpredictability of its actions, as well as fears about the rule of law. Perhaps most importantly, Congress seems set to make a bad fiscal situation worse. Given the strength of the US tech sector and likely AI-driven strength in US productivity, the story for growth-related assets does not seem to have changed dramatically, although lower population growth due to immigration restrictions is likely to slow the pace a bit. However, concerns about the US fiscal situation and the radical shift in the US policy environment are difficult to argue with.

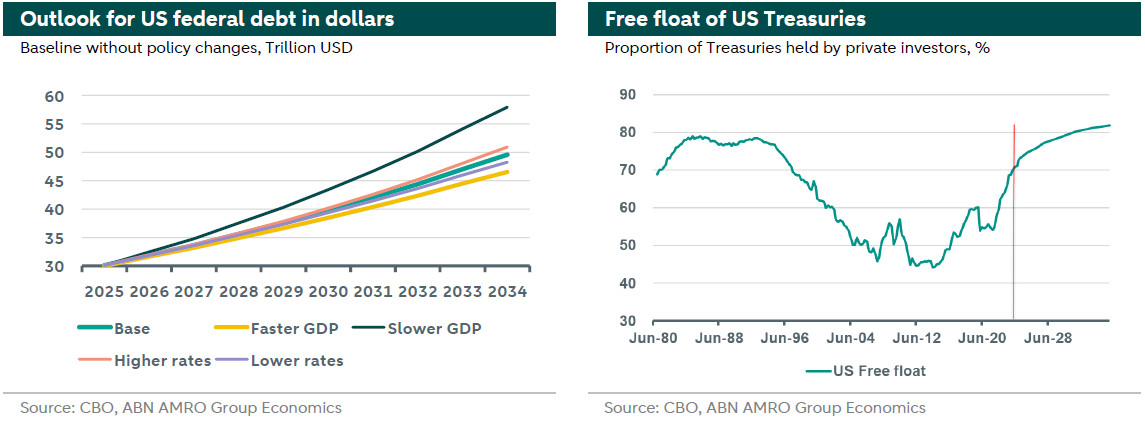

A lower dollar and higher risk premia on US Treasuries seem more likely than not going forward. Indeed, we have already seen the unusual combination of a weaker dollar and higher Treasury yields playing out, a phenomenon usually reserved for countries with shaky foundations or, put another way, weak ‘super fundamentals’. The focus of the recent discussions about US fiscal concerns has been the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), but it is important to note that it is the starting point that is the real problem. Even before considering the impacts of the bill, federal debt is set to soar in the coming years under the Congression Budget Office’s (CBO) baseline. In dollar terms, the outstanding stock is seen rising to almost USD 50 trillion from the recent USD 30 trillion. Debt rises sharply under all scenarios for economic growth and interest rates (see chart below on the left). At the time of writing, the OBBBA is still being debated in congress, but the latest iteration will likely add another USD 4 trillion to the debt between 2025 and 2034. According to the Committee for a Responsible Budget, if various provisions are made permanent, the cost would rise to USD 5.5 trillion over 2025-2034. The bill is still doing the rounds in congress, and is still subject to change. We think it’s likely that some version of the bill will ultimately pass – with the headline that it adds trillions in debt intact - although the latest developments have made it a bit less likely that it will happen before the 4th of July.

The projections above suggest that the supply of Treasuries will continue to accelerate strongly. Will the demand be there to smoothly absorb this supply? First of all, it requires investors to make Treasuries an increasing share of their asset allocation and they would need a price incentive - either through lower prices of the securities or a weaker dollar or some combination. Second, the structure of Treasury holdings suggest that price-sensitive investors have become increasingly dominant. In particular, the share of the foreign official holdings has been on a downward trend for some time, while the Federal Reserve has also been reducing its holdings. As a result, private sector holdings (also know as the free float) have risen significantly. What is more, even assuming that official holdings stabilize now, given the rise in supply, the free float is set to rise significantly further to reach levels even above those of the 1980s. Although the new supply will likely ultimately be absorbed, it will come at a price and it could well be a bumpy ride. (Nick Kounis)

6. What are the implications Dutch government collapse? Will we see a new cabinet in 2025?

Past elections suggest 2026 is likely to be well underway before a new government is formed.

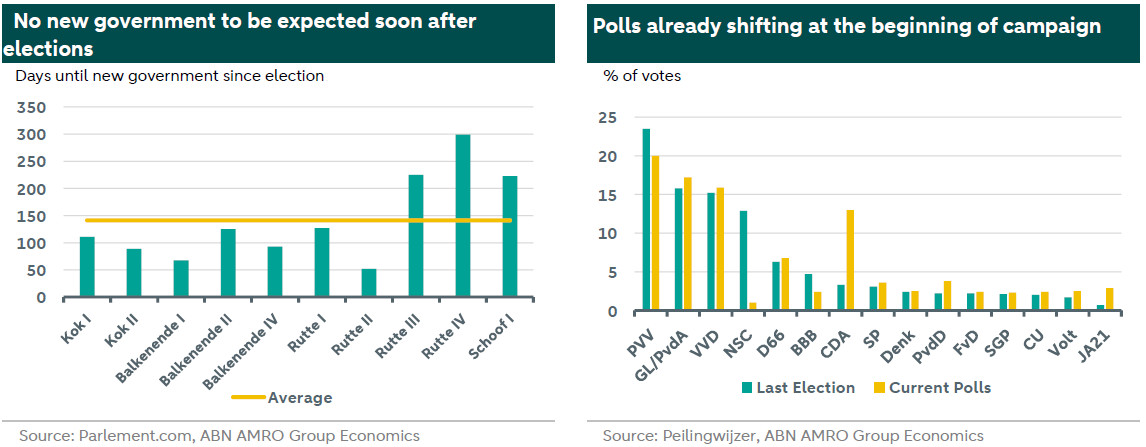

In early June the largest party in the coalition, the far-right PVV, exited the Schoof cabinet over a disagreement over migration. A multitude of reasons probably made it no longer feasible for PVV leader Geert Wilders to continue in the coalition. In the polls, support for the coalition – including the PVV – was declining. Moreover, the period ahead would probably be unfavourable for the PVV: 1) with conflicts internationally and the NATO summit in The Hague, the political narrative has switched towards national security and away from migration, the PVV’s main theme; 2) a multitude of spending challenges, for instance in ramping up defence spending, would make it difficult to execute Wilders’ generous social spending election promises. Following the collapse of the coalition, the Netherlands once again has a caretaker government. Since mid-2021 the Netherlands has had caretaker governments for roughly 40% of the time. However, we view the impact on the economy from the coalition collapse as limited (see Dutch regional chapter here), moreso this time as parliament intends to continue legislative work by declaring fewer topics ‘controversial’[1] compared to previous episodes when the government fell. This is important given the several supply side constraints that are holding back the economy. Still, the current situation leads to domestic policy uncertainty, at a time when international uncertainty is already elevated.

Looking ahead, elections are planned for 29 October and the political campaign is already well underway. After the elections a period of coalition negotiations follows. If the last 10 negotiation processes offer any guidance it would take at least until March 2026 before a new government is formed. Judging by the last three rounds this would be an optimistic scenario. More likely is that we won’t see a new government before next summer. (Jan-Paul van de Kerke)

Sustainability Spotlight: The macroeconomic impact of transition

Anke Martens - Senior Economist Sustainability - Aline Schuiling - Senior Economist Sustainability

Transitioning from fossil-fuel-based economic activities to sustainable energy sources while enhancing energy efficiency can significantly impact the economy

Depending on whether the transition is disorderly or orderly, there will be more or less economic impact during the first years of the transition

The transition is transmitted into the economy via carbon pricing and climate investment

Variations in monetary policy responses and the strategic utilization of carbon revenues play crucial roles in influencing economic outcomes

In the longer term, the economic impact of a Net Zero scenario is clearly positive

This Spotlight summarises our ESG Economist: The macroeconomic impact of transition

The fight against global warming and severe weather impacts requires a global shift from fossil-fuel-based economic activities to a clean energy-powered and energy-efficient economy. This transition towards achieving Net Zero emissions has significant economic implications.

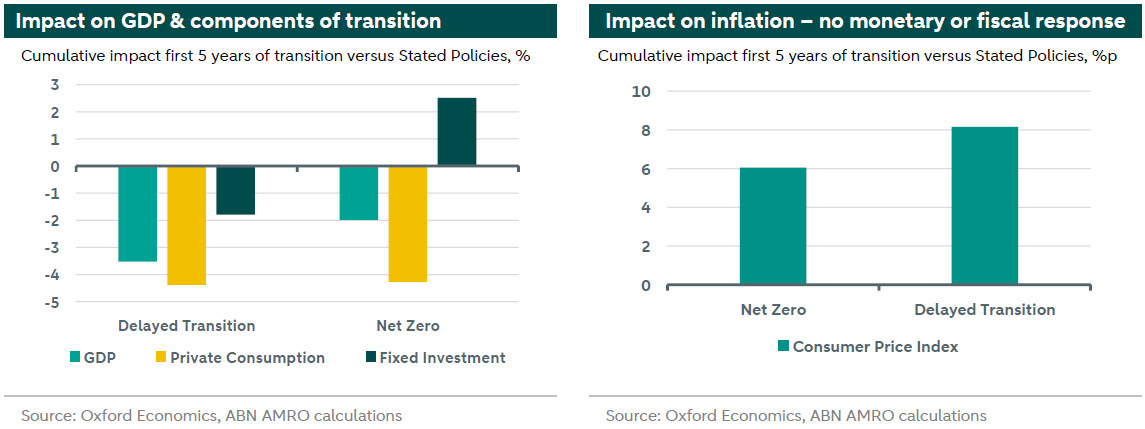

Orderly versus disorderly transition and the possible impact of monetary and fiscal policy

Transition scenarios can have an orderly or a disorderly nature. The chart on the left below shows the impact after five years in both orderly (Net Zero) and disorderly (Delayed Transition) scenarios, compared to a Stated Policies scenario, indicating that the negative impact on GDP of an orderly transition is smaller than that of a disorderly transition.

Key drivers of transition scenarios are the (shadow) carbon price and fixed investment. A higher carbon price increases the price of fossil fuels and energy, which pushes inflation higher (see chart on the right below) . Higher inflation, reduces real disposable income, and thus hits consumption. Investment, on the other hand, benefits from the transition even in the first part of the time horizon. This is because additional investment is needed for the transition. Across the economy companies, governments, and households will need to invest to shift to clean energy and enhance energy efficiency.

Central banks might respond to the temporary inflation spike with interest rate hikes, especially if they are already facing or fearing inflation overshoots. In the case that policy rates were hiked, the medium-term downward impact on GDP will be somewhat larger and the upward impact on inflation will be more limited. Besides central banks, governments can also have an impact on the changes in GDP and inflation, by either retaining the extra income from carbon revenues or recycling this back into the economy (also see our previous note about this here).

While the short-term impact of the transition may negatively affect economic activity and consumption, the long-term outlook is positive. As fossil fuels play a less significant role in the energy mix, energy prices decrease. Technological advancements drive productivity, investment, employment, and consumer spending. And importantly, the physical risks associated with other climate scenarios are avoided. In the longer term, Net Zero is clearly the preferable scenario.

[1] Declaring a topic as controversial means parliamentary work is postponed until a new government is in place. This process is to prevent having a caretaker government that rules beyond its grave.