ESG Economist - New NGFS scenarios: more damage, less time

In November, the Network for Greening Financial Services (NGFS) published the fifth vintage of its climate scenarios. The new NGFS scenarios have been updated taking into account the most recent developments and the country-level commitments as they stood in March 2024. A new damage function has been applied incorporating the most recent insights into physical risk damages.

In November, the fifth vintage Network for Greening Financial Services (NGFS) climate scenarios were published

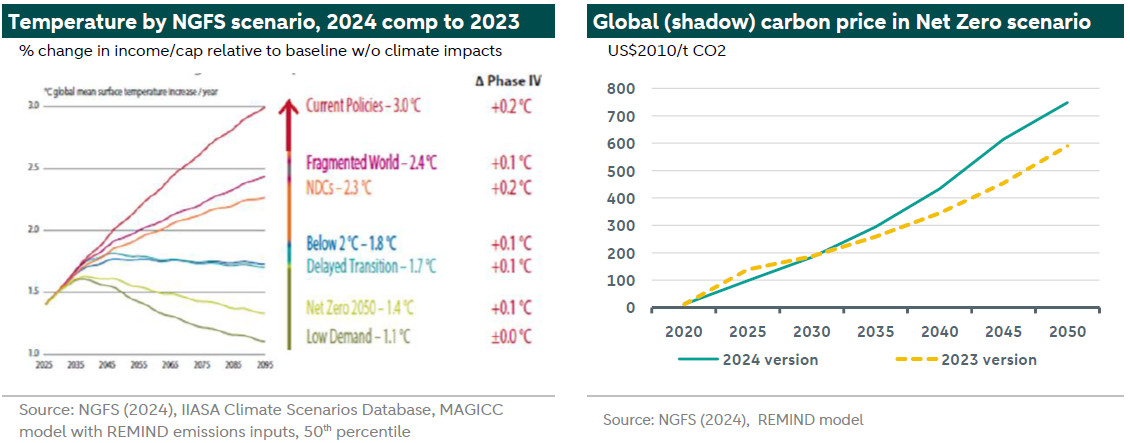

Temperatures associated with the various scenarios rose due to slow progress reducing emissions

NGFS uses a new physical risk damage function, which takes into account persistence effects and more transmission channels

Global damages from physical risk are 2-4 times larger than in the previous vintage, depending on the scenario

Temperatures across scenarios rose due to slow progress in reducing emissions

Compared to last year, almost all scenarios have a higher temperature increase associated with them given the slow implementation of climate policies, which has led to higher emissions in the near term. The research suggests that orderly transition scenarios are still possible, but require substantially more demanding efforts than delineated in previous vintages. That is, slow progress in implementing climate policies so far necessitates a more ambitious approach going forward. This implies a more disruptive transition than previously anticipated, and thus a higher (shadow) carbon price. As can be seen in the right-hand chart below, (shadow) carbon prices in this year’s Net Zero scenario are higher than in last year’s Net Zero scenario. This higher (shadow) carbon price results in an additional increase in energy costs (compared to last year’s Net Zero), which in turn puts upward pressure on inflation and causes an additional strain on the economy through decreased demand and market losses[1].

New damage function

The NGFS uses a new damage function for physical risks. This takes into account persistent effects and incorporates more transmission channels. In doing so, they are using the approach of for the first time this year. Earlier versions used the model of Kalkuhl and Wenz (2020). The work by Kotz et al. is based on the latest data from climate science and includes additional climate factors on top of mean temperature changes. Temperature variability, annual precipitation, number of wet days and extreme daily precipitation are also considered.

As mentioned, the new damage function incorporates more persistent effects of climate shocks, which means that it not only takes into account the instantaneous impact of a climate shock when it occurs, but also the delayed effects up to ten years after the initial impact. This feature is one of the important distinguishers of different damage functions. One of the reasons why physical risk damage estimates vary so widely is because of the “growth versus level” choice. A , for example, explains this variability. In it, it is found that various damage functions associate a 1˚C temperature rise with damage ranging from 1 to 45% of global output. When creating and estimating damage functions, the physical risk event either has an impact on the level of production at the time (i.e., the impact is one-off) or it has an impact on growth, for example, through productivity. The latter approach can result in a permanent impact.

The Kotz et al. damage estimates provide a middle ground between research that assumes level effects, and that assuming growth effects from climate shocks on economic output. Kotz et al uses empirical research that suggests that temperature shocks have a persistent, but non-permanent effect on GDP growth. They incorporate lagged (level) effects on top of the instantaneous shock. Their empirical analysis indicates substantial effects on economic growth at time lags of up to approximately 8-10 years.

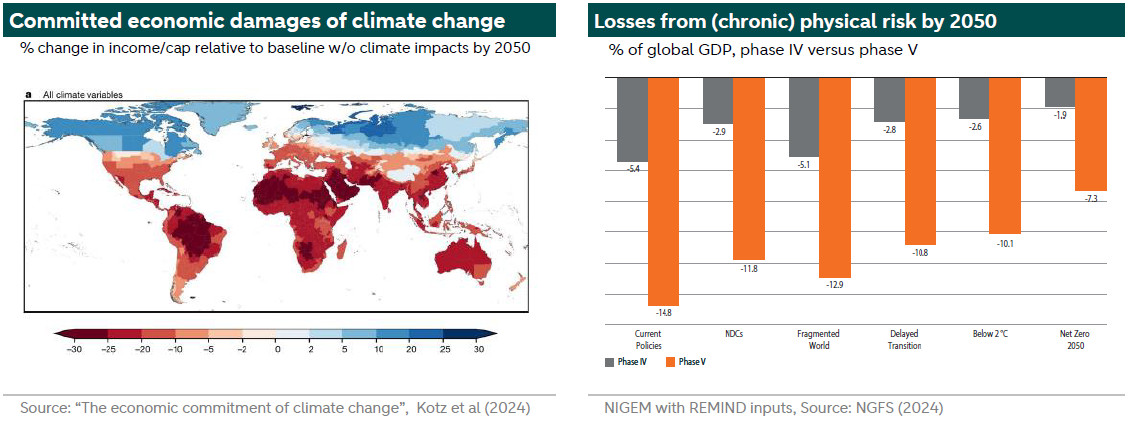

Global damages markedly larger

The new damage function projects significantly higher losses compared to estimates in earlier vintages produced using the Kalkuhl and Wenz (2020) model. The global damages from physical risks are two to four times larger than in the previous version, depending on the scenario. The losses projected by this damage function are in the upper range of estimates in the literature (but not the highest, see for instance an overview of damage functions on p14 of ). Hence, it is less likely to underestimate the potential negative consequences of climate change.

Under the Current Policy scenario, the global output loss was 5% for the year 2050, and in the new estimates, the global loss increases to 15%. For a Net Zero scenario, the projected losses increase from 2% to 7%. The increase is not across the board. Some northern countries actually see less damage in the new approach.

Still, while the Kotz et al. (2024) damage function extensively covers climate variations (e.g. temperature, precipitation), it may still not fully capture climate impacts. In particular, extreme weather events (i.e. acute physical risks) such as droughts and cyclones are expected to intensify as a result of climate change. Also, a number of other climate-related risks are not covered in this damage function, including climate-induced socioeconomic risks (e.g. migration, armed conflict) or climate tipping points. On the other hand, an underestimation of future adaptation could lead to an overestimation of losses. An additional complication compared to previous vintages is that the Kotz et al approach includes some but not all drivers of acute physical risk. As a result, a simple aggregation of this new damage function with the acute physical damages (which was possible in the previous vintages) could lead to partial double-counting.

[1] In some countries and time periods, the offsetting growth effects from carbon prices from carbon revenue recycling leads to a positive impact on the economy